On Sarah Waters by Charlotte Mendelson

We all remember where we were when certain books burst like a grenade into our consciousness. But I don’t think I have ever read a novel so powerful that I can still, two decades later, recollect the exact circumstances in which I reached a specific page.

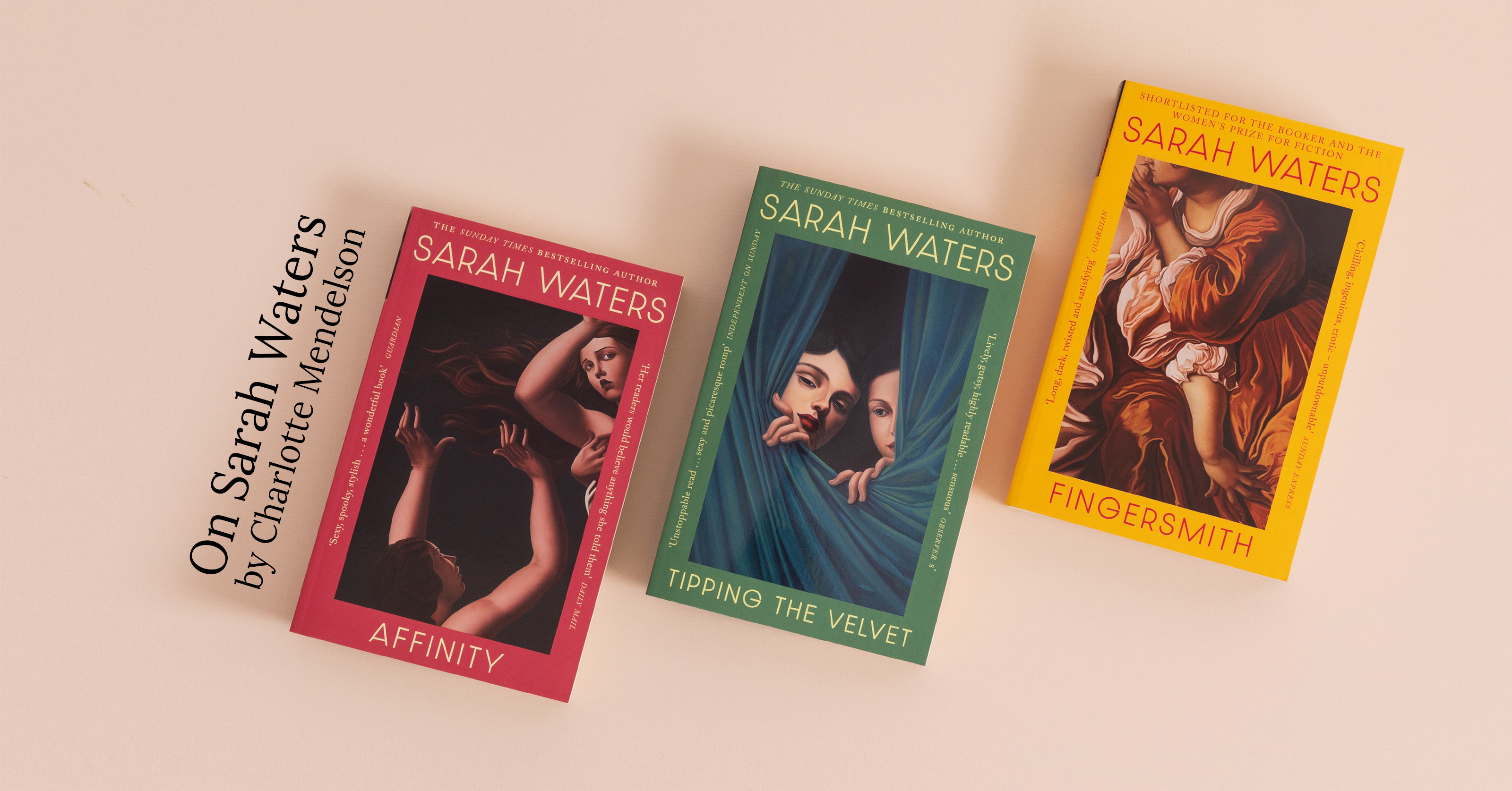

Other, that is, than Sarah Waters’ Fingersmith.

To understand the impact that it had upon me, you should know two things: my memory is appalling, and I am never, ever, speechless. But I can see myself now, on a very early train to Heathrow for a spring break: it was 2002, which means cheap linen and nasty coffee. Usually I choose my holiday reading badly; Fingersmith was a heavy hardback but I was more than a hundred pages in, and it was too engrossing to leave behind. Yawning, rumpled, with nowhere to sit, I was saved from grumpiness by Mrs Sucksby and her frightening baby-farm, the ambiguous, dangerous Gentleman, and Maud Lilly, an innocent in a dark world; by the elegant menace created by this exciting, daring, enviable author.

I’ve recommended Fingersmith hundreds of times’

I can still feel how the metal grille of the luggage rack dug into the back of my terrible fleece, see the westernmost reaches of London rushing prosaically past the window. And then I reached page 174, and that staggering twist. I remember gasping aloud, as if I’d been hit; not simply at the revelation, but at the masterly way it had been delivered. I was, I think for the only time in my life, completely lost for words. And that thrill has stayed with me: that shock

of a truly brilliant fictional twist which is one of life’s greatest joys.

‘Sarah Waters’ protagonists blazed a trail for writers like me; they also changed the landscape for countless readers’

Since then, I’ve recommended Fingersmith hundreds of times. And it isn’t even the Sarah Waters novel I adore above all. Choosing is almost impossible. The Little Stranger is a uniquely intelligent ghost story, teasingly refusing to define the nature of the horror it describes, while entwining it with the fascinating, unspeakable mess of traumatised post-war Britain: financial desperation, class tension, the first twists of insanity. The Paying Guests expands on the theme of genteel poverty, the small humiliations Frances and her mother endure, while slyly leading its readers to the edge of a stomach-lurching precipice of hope, transgression, the glint of desire, and pushing them off it. It’s precisely the slowness of the build-up to Frances’ terrible fall which makes this novel a masterpiece; a South London Macbeth, sexy and terrifying.

But my favourite of Sarah Waters’ novels remains her second, Affinity; the connoisseur’s choice. Shorter, subtler, set in neither the juicy darkness of the 1860s nor the sharp privations of the twentieth century, it encapsulates so many of the themes which she has made her own: how women are suppressed by, and slip around, the strictures of patriarchy, class and family; the violent madness of love; the attrition of social injustice; the way that sexual longing exposes the innocent to disaster. As twisty as Fingersmith, as perilously, coolly hot (almost) as The Paying Guests, I will always particularly love it for two reasons: it is the only novel which has ever made me truly believe in the supernatural, and it contains the sexiest line in fiction: ‘Remember … whose girl you are.’

And, now that Queer Fiction is more prevalent, it’s easy to understate how revolutionary these novels were. When I, and many like me, first wanted to read beautiful writing combined with same-sex desire, there was no shortage of gay male literary fiction, but almost no lesbian equivalent. Sarah Waters’ protagonists blazed a trail for writers like me; they also changed the landscape for countless readers.

Sarah Waters is one of the greatest living British writers; there is no other author whose every novel I have read, whose next work I am so twitchily impatient for. But, while I wait, I can at least go on rereading and recommending her, and I hope that you will join me.