Read excerpts from ‘Life and Story’ by Sigrid Nunez

“Life and Story,” is an essay by Sigrid Nunez, originally published in the Winter 2022 issue of the Sewanee Review and selected for the Best American Essays 2023.

Read on for two short excerpts:

‘Let me begin with an excerpt from a letter I once received from a former student:

When people have interviewed you, have you ever been asked, why do you write? Another teacher asked us that and it really made me nervous. So I said that the question really made me nervous and then answered in a kind of inarticulate way—I think I said something about feeling present. I’m not trying to covertly ask you that question but was just wondering if you are comfortable with it. If the answer is yes that would be cool because then I can feel like I might evolve in that vein. And if it is no that would also be good because I would feel like I was not alone in my feelings.

Immediately I thought of Flannery O’Connor’s response to a student who attended one of her lectures and who asked her this very question: “Miss O’Connor, why do you write?”

“Because I am good at it.”

“At once,” O’Connor said later, “I felt a considerable disapproval in the atmosphere”; but “it was the only answer I could give. I had not been asked why I write the way I do, but why I write at all; and to that question there is only one legitimate answer.”

I’m not sure why writers are so often asked to give their reasons for doing what they do. I don’t believe the same question is asked with anything like the same frequency of, say, visual artists or composers or performers. I have at times said that I write because it is what I know how to do, or because it is who I am, or because it has fulfilled this or that desire or need, and I have always been painfully conscious of how unsatisfactory these answers are.

You can read between the lines of the letter from my student, who was still in her teens, and who has clearly been led to believe that if she wants to write she should be able to state her motives. I want her to know that, first of all, she is not alone, that the question makes a lot of writers nervous or uncomfortable, that the same writer may have many different motives for writing, that a writer’s motives may change over time, and, above all, that the fact that she has no ready answer to the question is no reason for anxiety. I want her to know what George Orwell said, that “at the very bottom of [all writers’] motives there lies a mystery … some demon whom one can neither resist nor understand,” perhaps “the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention.”

I can say that I don’t remember a time when I did not want to write, and that it all began with being read to as a small child. Fairy tales, folk tales, classical mythology, children’s books—the ones about animals most of all. The wonderful Dr. Seuss. He was the first writer I ever tried to imitate, and I can remember saying exactly these words as a child: “When I grow up, I want to be Dr. Seuss.” Indeed, for years after this declaration, I thought children’s books were what I would write.

So, very early then, I equated reading with making people happy. And once I had learned to read myself, I discovered what a glorious thing it was to escape through a good book into some other world, at least for a time. It was a kind of double blessing: reading was a private, solitaryexperience, something you could withdraw into; and yet, when you were reading, you were never really alone. There was always the storyteller. There were always the characters. They were there when you needed them. They were your friends. And this corresponds to what I would one day learn about writing itself. The writing life appealed to me first of all because I saw it as something I could do alone, hidden, in the privacy of my room. But soon I discovered, as all writers do, that writing was an ideal way to escape the world and to be a part of the world at the same time.

…

Readers of fiction very often want to know whether a work is autobiographical, and if so how closely it hews to the author’s own experience. One of my favorite courses to teach is called “Life and Story,” with an ever-changing reading list of writers who have, to one extent or another, included elements from real life in their fiction—writers as different from one another as Primo Levi, Jamaica Kincaid, Teju Cole, Garth Greenwell, Akhil Sharma, Tobias Wolff, EileenMyles, Kathleen Collins, Renata Adler, Colson Whitehead, Weike Wang, and Alexander Chee.

What’s the big difference between life and story? I like what the Israeli novelist Aharon Appelfeld has said in this regard: “In life you can say it happened, but in literature you have to give good reasons: Why did it happen?”

Once, after the first class of a graduate fiction workshop I was teaching, one of my new students came up to me and said, “I’ve read all your novels, and I have to ask you something.” I thought for sure he was going to say something like, Is your writing autobiographical? Did any of what you wrote actually happen? Instead, he shocked meby saying, “Do you make some of that stuff up?”

Do I ever. I make a lot of that stuff up. In fact, I make up most of it. But in each novel I’ve written so far, like the writers I assign for “Life and Story,” I also used at least some material from my own life. And I believe Edna O’Brien got it right when she said that “any book that is any good must be, to some extent, autobiographical, because one cannot and should not fabricate emotions; and although style and narrative are crucial, the bulwark, emotion, is what finally matters.”

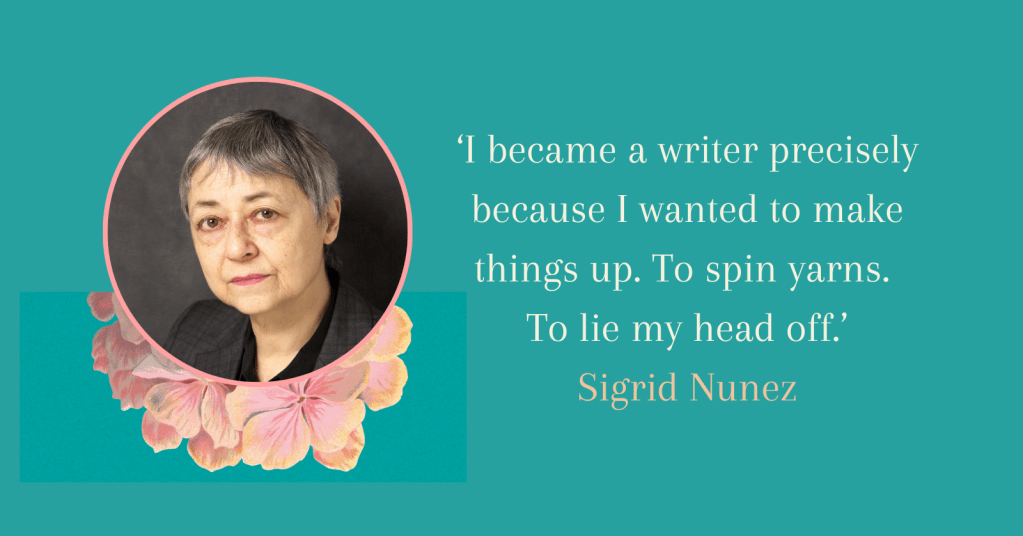

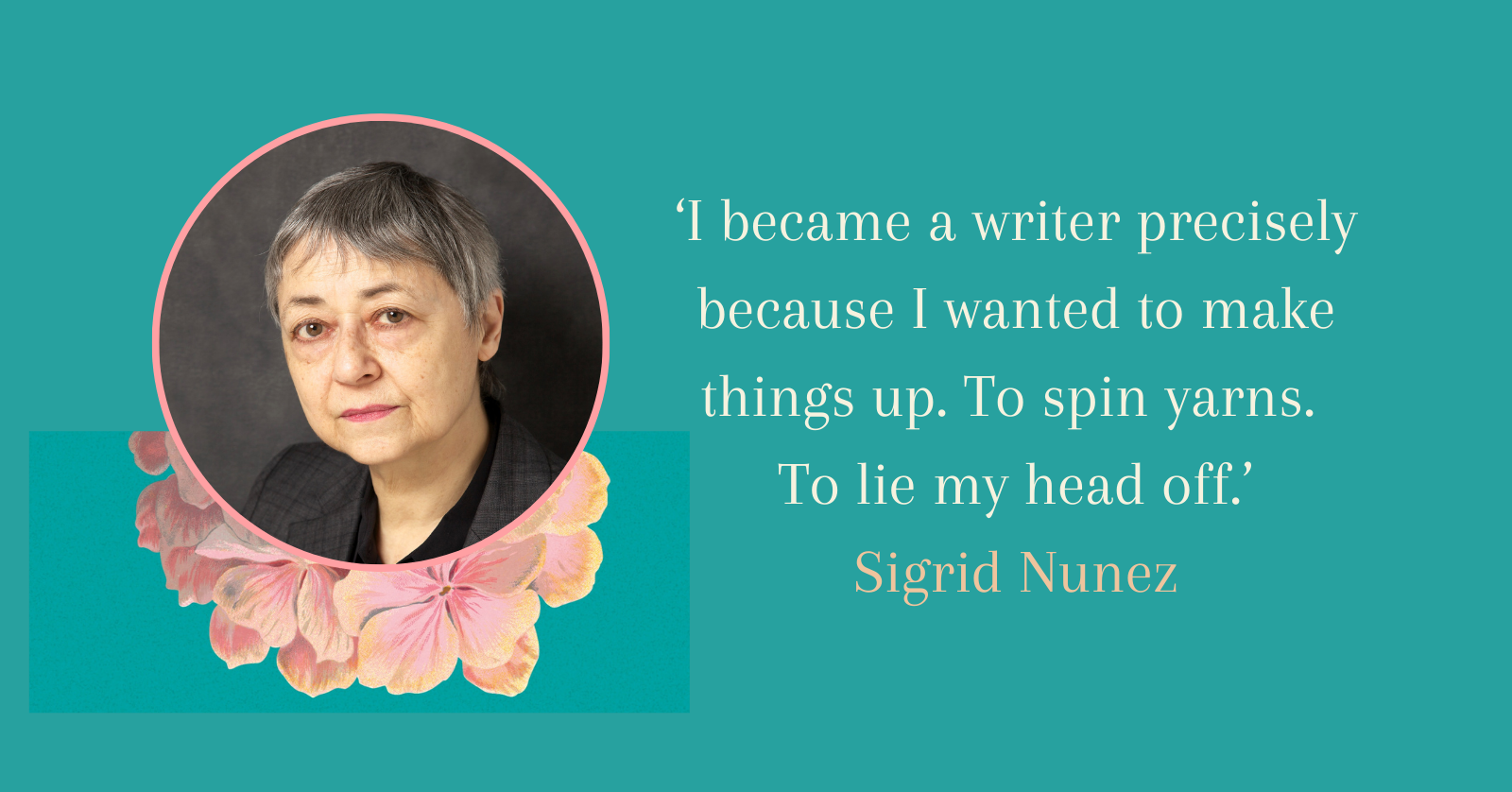

But no matter how autobiographical some of my writing has been, I didn’t become a writer because I wanted to tell what happened. I became a writer precisely because I wanted to make things up. To spin yarns. To lie my head off. And it isn’t memory that interests me most as a writer, but rather invention. I became a writer so that I could use my imagination. Remember, I wanted to be Dr. Seuss.’