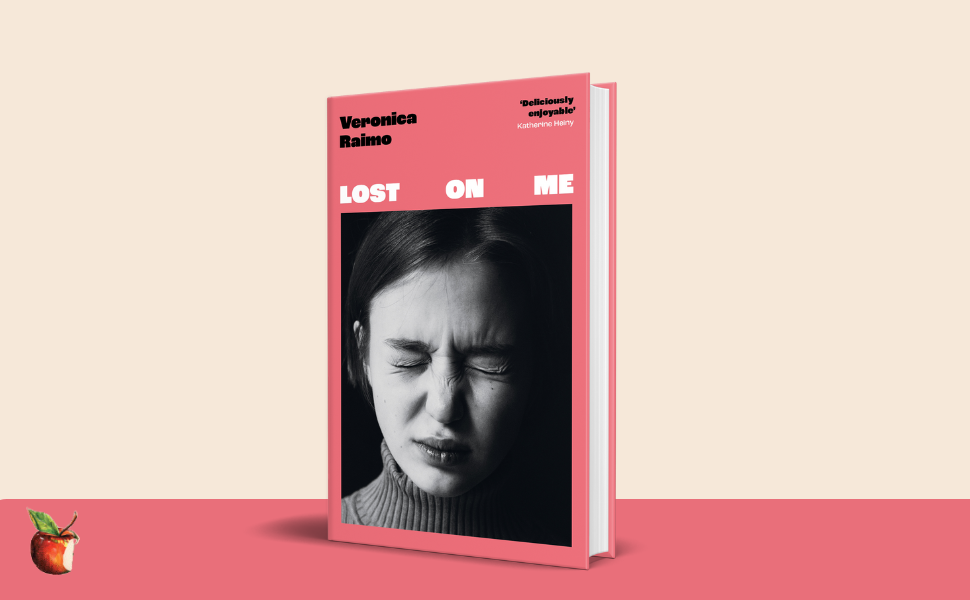

Read an extract from Lost on Me by Veronica Raimo

‘With combustive prose and oxidising wit, Veronica Raimo sets fire to the Bildungsroman. A clear-eyed comedic talent who bends the novel form to her will’

Naoise Dolan

A delightfully funny, bestselling, prize-winning Italian novel about sex, love, family – and how a writer transforms her life into art.

TRANSLATED BY LEAH JANECZKO

My brother and I both became writers. I don’t know what he answers when people ask him why that is. I say it’s thanks to all the boredom our parents imparted to us.

While my mother had high anxiety, my father had a subtler form of paranoia. His chemistry studies made him see the world as a petri dish of harmful substances we constantly needed to protect ourselves from. This meant leaving the house as little as possible, suffocating within four walls—or, in our case, a hundred.

I was eight at the time of the nuclear reactor meltdown in Chernobyl. Even when the emergency seemed to be over, my family continued to exist in a postapocalyptic film scenario, pretending we lived not in a relatively well-off city in the Western world, but in a sci-fi Zone X with high levels of contamination.

In every respectable catastrophe story, when the world’s been infected, all that matters is preserving one’s blood ties: the family. And so for three years my father didn’t let us eat fruits, vegetables, or eggs, or drink milk, or go out to restaurants, or buy pizza from street vendors. The only foods allowed were canned goods dated before April 26, 1986.

It wasn’t easy to follow this protocol, but I must confess that it made things interesting, made me feel like a heroine living in a state of quarantine invisible to the rest of the world. Staying entrenched in our secure apartment, eating tuna and beans like the pioneers, coming up with outlandish excuses to turn down a snack when studying at a classmate’s, or checking the packaging dates at the supermarket as though they were secret codes meant just for us, the chosen few.

We all ended up with a pretty bad vitamin deficiency, and though my mother drugged us with Be-Total and Co-Carnetina, we were all a bit green around the gills. Still, we survived. Worst-case scenario, we risked coming down with scurvy.

Thanks to our strict upbringing, neither my brother nor I ever learned to do such hazardous things as swimming, riding a bike, skating, or jumping rope (in a flash we might have drowned, cracked our skulls, broken a leg, strangled ourselves).

We spent our childhood cooped up at home, bored off our asses. It was such an all-consuming activity that it soon became an existential pose. We knew how to be bored like nobody’s business.

In our building there were always kids playing down in the courtyard, and their shouts and cries reached our ears like some strange animal language we didn’t understand. We would spy on them from our sliver of a window, in silence, the lights out. We would take turns raising our faces a few centimeters above the windowsill (there wasn’t room for us both) to then duck down if one of the kids looked up as they followed the arc of a ball sailing through the air. We were terrified by the thought that they might see us, because we wouldn’t have known how to handle an invitation to join them. Two little spies barricaded inside their home.

The worst part is we never even saw ourselves that way. I mean, we could’ve turned it into a game—“Ha! They didn’t see us!”—enjoyed the thrill of not getting caught, debating who was the cutest boy or girl in the group, at least as much listless diversion as old men staring at a construction site. But no, not even that. We were just two kids who were really good at being bored off their asses.

One day, from the secrecy of our hiding place, we faced an appalling moral dilemma. The kids in the courtyard were playing soccer with a toad. At first the animal was simply placed in the middle of them all, surrounded, like the typical loser in an episode of adolescent bullying. The toad hazarded a couple leaps, but it clearly had no escape plan. Then, from the circle of legs, the first kick swung out. They started dribbling it to one another. What reached our outpost were more the idiotic little shouts of humans than the thump of a shoe making impact against the creature’s warty flesh, or the splat of its body against the asphalt when someone missed a pass, but in my head it was all loud and clear. My brother and I squeezed each other’s hands throughout that endless torment. I think he was praying. I could hear him mumbling litanies, though he didn’t make the sign of the cross because I wouldn’t let go of his hand. I just wished the toad would die quickly and put us out of our misery. We couldn’t breathe. Or better, we deliberately chose not to. Cowardly and hopeless, as always. So was that what our parents were trying to protect us from? The discovery of evil in our own courtyard? The horror, the horror!

When we finally discovered books, it wasn’t a form of escapism, but rather the reassuring coalescence of boredom. I could almost picture it in my mind, white and miry: reading was like sinking into a pool of milk. I would stay immersed for hours, until even my body grew flaccid, the stagnant liquid seeping into my pores. It felt like everything suddenly acquired meaning, a phenomenon of transubstantiation, my flesh changing into boredom. I couldn’t say whether I liked a book. That was never the point. In fact, I imagined that attempting to derive any pleasure from reading would have been a lost cause. Why bother trying? Besides, there was one thing my family feared even more than the toxic cloud from Chernobyl: hedonism.

Before books came along to dope us with boredom, my brother and I came up with other pastimes.

The family genius had invented a game that took up our afternoons for several summers. From right after lunch-time until the sun went down, and up to the point when we needed to go have dinner, we would lie on the floor side by side, propped up on our elbows with a notebook in front of us to play the numbers challenge. We didn’t play against each other but beside each other, because the game wasn’t competitive. Actually it wasn’t collaborative either. It was more like the Zen exercise of counting sheep jumping over a fence when you were trying to fall asleep. You rolled a die and marked down the number that turned up. We spent hours doing it. Committed, engrossed. We were both big fans of five, so the only real highlight of the game was hoping the five turned up as often as possible. Which showed its superiority. As I rolled my die, I would peek at my brother rolling his, would sense in his focused gaze the hope that it would be a five, followed his steady, honest hand marking an X below the number four. Barely a glimmer of regret in his eyes and then, with perfect faith, ready for the next roll. Careful not to be seen, I would mark an X in my notebook below the five, lowering a curtain of fingers in front of my die, which had landed on a pitiful two. I was capable of cheating at a Zen game. It was senseless. Still, I couldn’t help it.

When my parents called us to dinner and he and I compared notes, my five always came out the winner. I don’t know if my brother knew I was cheating, or if he couldn’t even have fathomed anything so petty. He tried to decipher the data and was surprised at how it defied all statistical probability. He tried to discern another possible logical explanation, attempted his first forays into metaphysics. How could I have rolled a five so many times? Then he would pat me on the back and say, “Brava.”

I’ve often thought about that “brava.” I’ve wondered whether it was due to the principle of communicating vessels, whether my brother needed to force out a “brava” or two every so often to make room for all the others being directed at him. I’ve also wondered if it was one of his first manifestations of sarcasm. Involuntary, perhaps. I’ve wondered whether he actually wanted to tell me “brava” to praise my silly trick, my attempt to overcome the boredom of his inane game by doing something even more inane. Whether he was trying to say to me: how can we escape this bedroom? How can we break free?

Actually, that’s what I’ve been doing my whole life. Whenever I feel like I’m trapped in a room, in a game with rules rather than trying to escape from it I try to taint the logic of the room, of the rules. To imagine things that aren’t true, to say them, cause them, until I believe them. Until I believe a die can always turn up five, even though it makes absolutely no difference at all.