Read an extract from A Green Equinox by Elizabeth Mavor

‘Elizabeth Mavor relishes spirited, unorthodox women, free with their tongues and ready to snap their fingers at convention’ LONDON REVIEW OF BOOKS

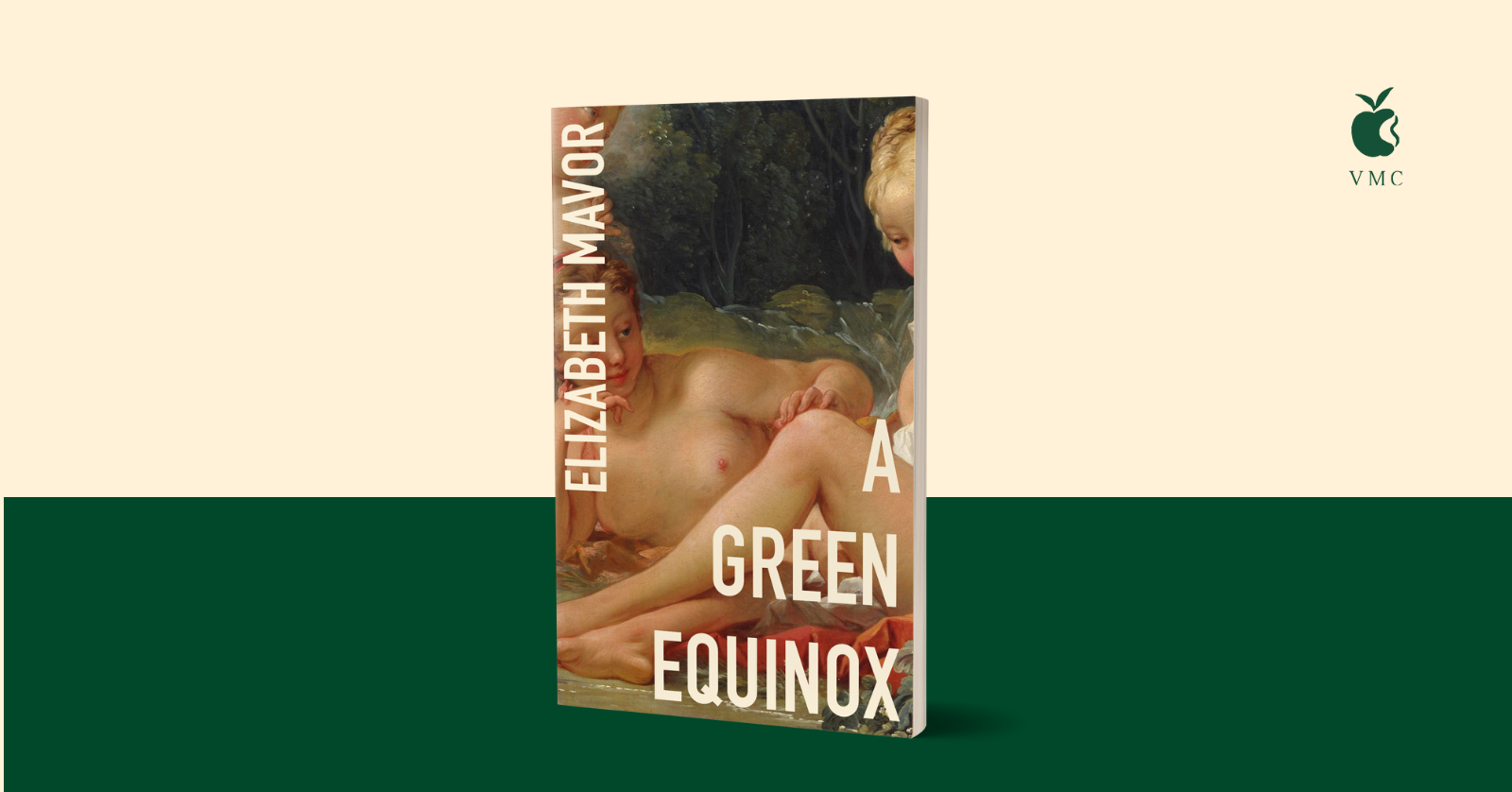

An intrepid exploration of gender, female sexuality and passion: romantic, carnal, and cerebral. This brilliant novel, long out of print, was shortlisted for the 1973 Booker Prize and joins the Virago Modern Classics list in September.

ONE

Last night while you were asleep I lay awake beside you planning your epitaph. I saw the words in Gill chiselled into the stone of the urn containing your ashes, and beside the urn, pouring its leaves over you, a willow. In a sort of pleasurable grief I tried out the various possibilities; first high Italian sentiments, then French, then Latin (‘non sum, non fui, non curo’ halted me for a moment; I like that. ‘I am not, I was not, I care not’), then I moved on to the little Greek I know. I rejected this, however, because no one would understand it nowadays, and I’d want them to know what you’ve been to me. I also experimented in the phrases, convoluted as broccoli, of Sir Thomas Browne, and in the neat unexcitable periods of Pope, and finally I tried to compose in the bloodless contemporary jargon in which you and I have to speak to one another, my own love. You who are not yet dead.

It was an indulgence I enjoyed. You would have despised it, for much as you love trees you’d object to the willow, and the urn would only make you laugh. I remember quite well how you mocked just such an urn with your walking-stick in a Welsh graveyard: a vast, breasty, buttocky pot it was, teetering on an inadequate stone stalk and swollen like a pink granite womb with the romantic bones of some Georgian parson’s wife who insisted on direct descent from Cadwallader. It only served to show, you said at the time, what a fatuous attitude people have towards death.

Death. At that point I gave up writing epitaphs and lay back beside you, and while I waited for sleep I retraced the road which brought me to you. Unbelievably it took only six months, equinox to equinox.

It had its starting-point late on a March afternoon at the end of a still, mizzling day. There were four people in the shop cropping along the shelves, and I was turning over the pages of a broken-backed book of early flower portraits, unable to make up my mind whether to break it up for prints or to take the trouble of repacking it. To destroy it or not, but I love what is old. I should explain straight away that I have the Great Sickness. No, not that particular sickness, though there have been moments in my life of such amorous idiocy that I probably deserved even that. No, I allude to that far worse sickness for those afflicted with it, that passion, that love affair, sexual almost,with the lost past. Friends have, of course, tried to persuade me that if such a passion is not a sickness then it’s a sin, like hubris or tristitia or worst of all accidie, that devilish torpor, that restless sadness, which of all of them perhaps most nearly resembles what I suffer from, and they have advised me to stop squandering my vivacity and intelligence and, instead, discipline myself by bringing up a child, or doing social work. I, however, have read Freud carefully, and I think differently, and I know that it’s not sin but a sickness, with symptoms.

Of course there’s something wrong, some imbalance, or why else should I gorge myself on second-hand books of history and travel and topography, even on old floras, seeking a world that I can now never, never inhabit. I remember one book particularly, Reckitt’s Guide to East Anglia I think it is, which tells you how nowadays (c. 1911) you can hire a wherry that can sleep eight and has a crew of two and a grand piano, all that for just three guineas a week.You can get there direct from King’s Cross and buy a luncheon basket at the station with cups and knives and spoons and glasses, chicken, hot bread rolls, mustard, apple pie and a bottle of Beaujolais for 3/6 a head. Then not long ago Ifound Trimmer’s 1869 Flora of Middlesex, and I read there that ‘the Meadow Orchis is abundant!’ round Pinner; that ‘it is plentiful!’ in a meadow near Hendon; and that the rare Viola palustris is still flourishing behind Jack Straw’s Castle on Hampstead Heath. There is a pencil note in the margin at this point which says, ‘Still there 1892. Wood-Smith’. ‘Still there . . .’ How can I express the sweet anguish aroused by those doomed words, ‘Still there . . .’? The shop door swung open and someone came in, closing it carefully behind them. For a moment I didn’t look up because I was so deep in my moral debate as to whether or not I should destroy that book of prints. Eventually I laid it aside and raised my eyes.They were trapped instantly and held, by those eyes, blue and water-clear, of the Enemy.

For a moment only I was appalled. Yet it was just sucH a confrontation that I’d feared for two long years now, though as time went on I’d become accustomed to fearing, the keenness of my alarm diminished perhaps by so frequently seeing her shopping or motoring through Beaudesert with her children. Soon, and shamefully, because it almost always does, the appalled feeling began to giveway to one of amusement, for to be fair it was not she but I who was really the Enemy though she wasn’t to know it. Now, did this sort of thing concern me? Did I think I could be interested? she was asking me. She had, as I would have expected, the usual rather belling upper-class voice, the kind of voice one knew she’d have by merely looking ather. Concerned, as it happened, I was not, for very good reasons that I would be prepared to give, though I didn’t say so then. Interested, of course, though not in what she seemed to be talking about (Race Relations, Pollution, H-bombs, perhaps even Noise Abatement). In her, however, I was interested. I was face to face after all with the woman who could destroy my peace.

Hughie hardly ever spoke of her, partly because he was too good-mannered, partly because I think he thought I’d be jealous. When he did speak of her it was always and deliberately with affection. Theirs was an old marriage to ponder, for it seemed that, while he quite genuinely loved her, he was at the same time dreadfully bored with her. Belle was Catholic. Unfortunately she was not only a convert but an avant-garde one, which was very bad luck for Hugh, who would so much have enjoyed meeting Establishment Catholics, people like monseigneurs and wonderful reactionary old bishops who like you to kiss their rings. As it was Belle appeared to be absorbed in the secularisation of practically everything that was in any way arcane or ritualistic, and regularly attended gatherings in already secularised country houses to achieve this end, something that could in no way appeal to Hugh.

Looking at her in those first short moments I thought, Oh yes I know you! Oh yes! An external, a useful, an uncomplicated, a clearly-charted life. Here, I knew, was somebody who believed in planning, in the future, in the dignity of man. O Holy Britomart! She was fair, big-breasted and scrubbed. Nordic. What virtuous nourishment would ooze obligingly from those globular breasts. Mine were trim and neat and rakish, because they’d been used only for making love and not feeding children. Their aureoles were turkey brown as befitted an adventuress, while hers, I knew, for all that they should have gone brown bearing children, would still have the sucked pink look of uninterfered-with virginity.

‘As you can see, this sort of thing—it’s mainly a question of publicity,’ she was saying. She spoke extremely clearly, in a voice which was like flawless bronze, softly gonged. ‘On the whole people seem pretty keen,’ she said. I bet, I thought with cooling heart, for ours is a keen little town composed as it is almost entirely of one class, the intelligent if not always cultivated middle. This is due to the Chemical Weapons Establishment nearby which succeeded the gravel workings which once provided Beaudesert’s livelihood. These were discontinued some time ago leaving ravaged meadows eaten out with water-swamped fistulas and pits upon which the keen chemists sail Fireflies in the summer, and where, in winter, they watch widgeon through expensive Ross binoculars.

I am sorry that Aristotle in the Politics was not more specific about the desirable proportions of class and occupation within a community. It does seem so very important to get it right, for while a preponderance of what are now called ‘manual’ workers seems to produce a dispiriting sameness, only occasionally spiced by that degree of eccentricity (gnomes, grots, parterres, gig wheels) which the local authority permits, too much of ‘non-manual’ is almost worse, just as enervating, producing such a sense of non-movement, of petrifaction. Although I own a bookshop and shamelessly live off the cultural aspirations of the inhabitants of Beaudesert, although one part of me does want to rescue what is left of the charmed past, I am nevertheless dispirited by those too perfect Georgian streets so assiduously protected by weapon dons on the C.P.R.E., and this also goes for the careful street-lighting and the all too consciously pleasant car-free shopping precinct.

Hughie, who beneath his teasing exterior is just as wolfish an enemy of the times as I am, is constantly rubbing it in that I’m really a monster of destructiveness, that I would actually prefer all that is left now to fall into a picturesque decay rather than that the beautiful ancient, which I adore, and which I believe can only be the inheritance of the Few, and of those Few, only the very Few, should be dolled up and given a face-lift for the benefit of the disgusting Many.

He has really no right to talk like this, having shut himself away from all hurt and disappointment in the fastness of Beaudesert Park, appointed guardian, by a wealthy and discriminating Trust, of the sacred flame of culture which flickers fitfully inside what, to my way of thinking, is one of the most hideous and lowering buildings in the country. It arose, the fruit, one can only guess, of penal labour, late in the sixties of the last century, in the chateau style, and upon the ruins of something far older and, one trusts, more beautiful.

The original Beaudesert Park through the preceding centuries had been added to, partially pulled down, rebuilt, renovated, modernised and finally burnt to the ground by a pyromaniac stable-boy, leaving only its great name, its escutcheoned entrance gates, and the remains of grounds in the Kent manner protected from the advance of the despoiling gravel operations by ha-has. The Park does house, however, protected by extremely savage alsatians, bells, tripwires and ex-Guards sergeants, a splendid collection of Louis Quinze furniture, paintings and books.

It was through books, beautiful but so dangerous books, that I first met Hugh.

‘It would be exceedingly kind if you really would,’ Belle Shafto was saying now. This was her expressing gratitude for my agreeing to put a notice of her (protest?) meeting in my shop window. I hadn’t realised until nowthat she had a small child with her (there were two self-possessed older ones away at what were bound to be progressive schools). This one was very small and self-possessed and of uncertain sex owing to warm clothing. A barricade of old copies of the Illustrated London News had concealed its activities from view until now. It was engaged in caressing the yielding cream belly of the shop cat, and when it suddenly looked up I saw that it had Hughie’s golden eyes, which made me feel oddly, not because I have ever wanted children for I haven’t, but because those quiet gold eyes were windows into a room, one that I, the mistress of my love, with my timed secrecy, my fruitless pleasure, was shut out from. I knew, who doesn’t, the chaos of crying and wetness and anxiety, the deadly tiredness that pervades such rooms, but at that moment I also glimpsed something else, an unfamiliar and rather loving dimension of sex, private rather than secret, gentle rather than passionate. Also tender, singing, comfortable, a room where in mutual tolerance past and present and future were seamlessly knittedup. It may only have been the interest that a childless woman sometimes has in the woman with children, or again it may have been the perennial and mutual fascination that the wife holds for the mistress, the mistress for the wife; but whichever it was I turned back to Belle and found her for the first time mysterious, almost intriguing. ‘I don’t suppose,’ she was asking with her frank gaze, and she smiled, cleanly and whitely, in a way that was snow and sharp-cut fir trees, whilst I by comparison was a messy Neapolitan back street, ‘I don’t suppose that by any chance you’d like to come to our meeting?’ I honestly didn’t know what it was I was being asked to (Unmarried mothers? Dangerous toys? Abortion? Pink-foot geese? There are new ones every day); it could have been anything, but curiosity, also amusement, also, I realise now, a desire both sweet and wicked to tempt fate, made me say quite uncharacteristically, Yes!

After she’d gone I found myself wondering whether Hughie would laugh about this or be angry. We had agreed long ago that his wife and I were bound to meet some time or other, living as we did in such a small town, she a semi-public woman because she was married to the gauleiter of Beaudesert Park, and I semi-public too because of owning the only bookshop in the place. Actually it was amazing that we hadn’t met before. What Hugh would say at once, of course, was that although our meeting had always been likely, probably inevitable, I needn’t have immediately committed myself on Belle’s account to an occasion concerned with something (Nuclear tests? Gay Lib? Dyslexia?) in which I had not the slightest interest. Why in God’s name had I done it? I am not afraid of Hugh, but I do love him I think. In the end I’d probably turn chicken and cancel the whole thing. I hadn’t, after all,actually promised to go. So for a time I dismissed it from my mind.

Until now Hughie’s and my assignations had been hardly deserving of so colourful a name. They were simple and easy to effect. The library at Beaudesert was not only an antiquarian but also a working library used by scholars, and it was in need of regular attention, the kind of attention my small but specialised business is so very well qualified to give. Not only do we provide the leather restorative (an acidless receipt given to me by an old Florentine collector) but I also repair and bind the books myself. Long ago that passion which I have for the beautiful ancient led me to learn bookbinding, and since then I have not only equipped myself with all the necessary tools of my craft, but I have also one of the finest collections of antique fleurons in the country. I began acquiring them some years agowhen all the other binders, seeing no further use for them, were throwing them out by the boxful—all the minuteurns and willows and suns and roses and fish and harps which in gold had embellished the leather spines of eighteenth-century books.

Hughie, like me, also collects, but in the more esoteric seventeenth century, thus communication between us is not only an affair of great pleasure but of enjoyable business. Belle, I had always understood, while admiring and encouraging Hugh’s interest, has, as one might guess, little use herself for the fine page or the beautiful binding. The books that she consults are honest, unpampered creatures which have to work. Paperbacks.

Hugh did in fact come that night. There was a volume of Shenstone that needed re-backing. He came by the side door, because by then I’d closed the shop and withdrawn into my eyrie above, where I have a small flat with the usual offices and a pleasant parlour-like room lined with the best books.

It was to be an off night. Hughie had already eaten, and I had nothing suitable to drink on top of one of Belle’s pilaffs, which were apt to be distending. In addition he was in a state of siege neurosis having just had a letter from some kind of educational organisation demanding, literally demanding, a five-day residential course in May on eighteenth-century books and furniture. Because of this, but also, looking back, because of some instinctive disinclination of my own, I put off telling him about the day’s meeting with Belle.

It was to be an off night when we lay together too. Perfunctory. This had already happened sufficiently recently to make me unhappy, despairing momentarily, as one does, of ever having again the marvellous and secret honey which we had once shared together. He could be a precious lover, and, unlike the others, could recreate from my body, neat, self-contained and selfish as in the beginning I think it was, a landscape from Paradise. One in whose leaves and secret rills and trembling sunlight we had laughed and bathed together, ravished.

‘Oh God! Oh God! Oh God!’ he cried when it was over. ‘What on earth’s the matter?’

‘Five bleeding appalling days!’ He described them, beating the air with his neat legs. Each one of them would be a triple crucifixion. How he hated everything now! How he had got to hate culture itself, which was after all his bread and butter. Cried out how he loathed all their beastly expressions, the Rewarding, the Enriching, the Meaningfulness.‘But the Feeling!’ he yelled. ‘The Feeling!’

‘Kiss me again,’ I said, ‘and then you can tell me about it.’

‘Surgery! Concept! Probe!’ he replied, ungratefully. ‘Bottleneck!’

‘Dialogue!’ I said, stroking him.

‘Skills!’

‘Skills came in,’ I said, ‘and Skill went out!’

‘I love you!’ he suddenly said and laughed.

‘Not actually my joke,’ I said. ‘An old sour one by now!’

‘I know it is, but I still love you!’

‘Only because I pander so slavishly to your deathly meanness, your prejudice, your backward-staring.’

‘You listen to me! You take my word for it! It’s later than you think up here in Joyous Garde. They’re only waiting to mine a great breach in the outer walls and then they’ll all pour in and plaster their filthy hands all over the sacred treasure of the ages.’

‘You might say they’ll plaster their sacred hands over the filthy treasure of the ages,’ I said, ‘and anyhow, who are “They”?’ I interlaced my fingers with his.

‘“They” are not “Us.” We are the last of the truly lovely people,’ he said and lit a complacent cigarette.

‘Actually we’re not lovely at all,’ I said, though as a matter of fact he was lovely. ‘We are arrogant and overprivileged.’

‘That’s what I call lovely nowadays.’

‘We are mean and splenetic and selfish; indeed we are dross.’

‘Dross? Dross? O lovely, lovely Dross!’ and he kissed me again. ‘Think of them all in their working-parties and workshops, all their sit-ins, pray-ups, fall-outs, and all they’re actually doing is colonising. If only they could see themselves for what they really are, the New Imperialists. That’s where all the energy of the country’s going, in Aunt-Edna-like Imperialism! So thank God, thank God, for the Dross!’

‘Well, well, what is it you believe then?’ I asked, and entangled his long hair gently in my fingers. Such fine silky hair, and he had long lashes, and a long thin mouth which, when he was going to laugh, puckered viciously at the corners as though he’d just sucked a lemon.

‘I believe in Michaelangelo,’ he began, dreamily closing his eyes, ‘in Velasquez and Rembrandt; in the might of design, the mystery of colour, the redemption of all things by Beauty everlasting’—what great stuff! ‘But oh!’ he cried opening his gold eyes, ‘if only I did! No, you must ask me something much more interesting. Please ask me what I don’t believe in!’

‘Precious love, what don’t you believe in?’ I had of course heard it all before.

Certainly not in the dignity of man, nor in man’s rights, nor in man’s bottomless capacity for improvement, nor yet in man’s natural goodness, which is ascribed to his human heart. Above all the heart must not be believed. It was perhaps the heart he dreaded more than anything. The sleep of reason produced monsters. He was terrified of the feeling heart.

‘All the words they use!’ he cried sitting up. ‘Every one of them a great kick on the scrotum!’

Disturbed! Handicapped! Unacademic! Disorientated! As though what was criminal, mad, stupid and cruel, had been eliminated from the world by the mere use of these words and the millennium come at last, which it hadn’t.

‘Say just that then,’ I said, ‘say that at your five days’ wonder.’

‘And Belle’s such a sucker for all these words,’ he said moodily. ‘She uses them constantly; it really gets on one’s wick.’

‘Well?’

‘Well, I’ll think about it. About how to say it I mean. Poor Belle!’ he added.

It occurred to me then that it would be even more difficult now for me to tell him about my meeting with his wife and the subsequent rendezvous we had planned. ‘But O lovely! O wild! O secret! O dark, dark barbarian! My ambiguous Hero!’ ‘Romantic fool!’

‘So wilful, so mad and bad and dangerous to know!’

I could have loved him again then, and I dare say it would have been much better than before. I am a little like Madame de Warens, who was able at any time to interrupt a discussion on art or whatever to make love, and then could resume the interrupted discussion immediately afterwards as though nothing had happened. Hugh, alas, was not like this. The unpleasing euphemisms we had been discussing had upset him, and he went. He left me alone in our white crumpled bed listening to the fine rain of the spring night flying like scattered poppy seeds against the window.

I lay still for some time after the door had closed and then, too restless to sleep, I got up and went downstairs into the dark shop where Belle’s notice was still lying on the counter. It turned out to be all I had feared. Waiting to spring like some disagreeable jungle creature from its liana-like forest of jargon, was an invitation to meet, in order to love, over tea or coffee, one’s neighbour.