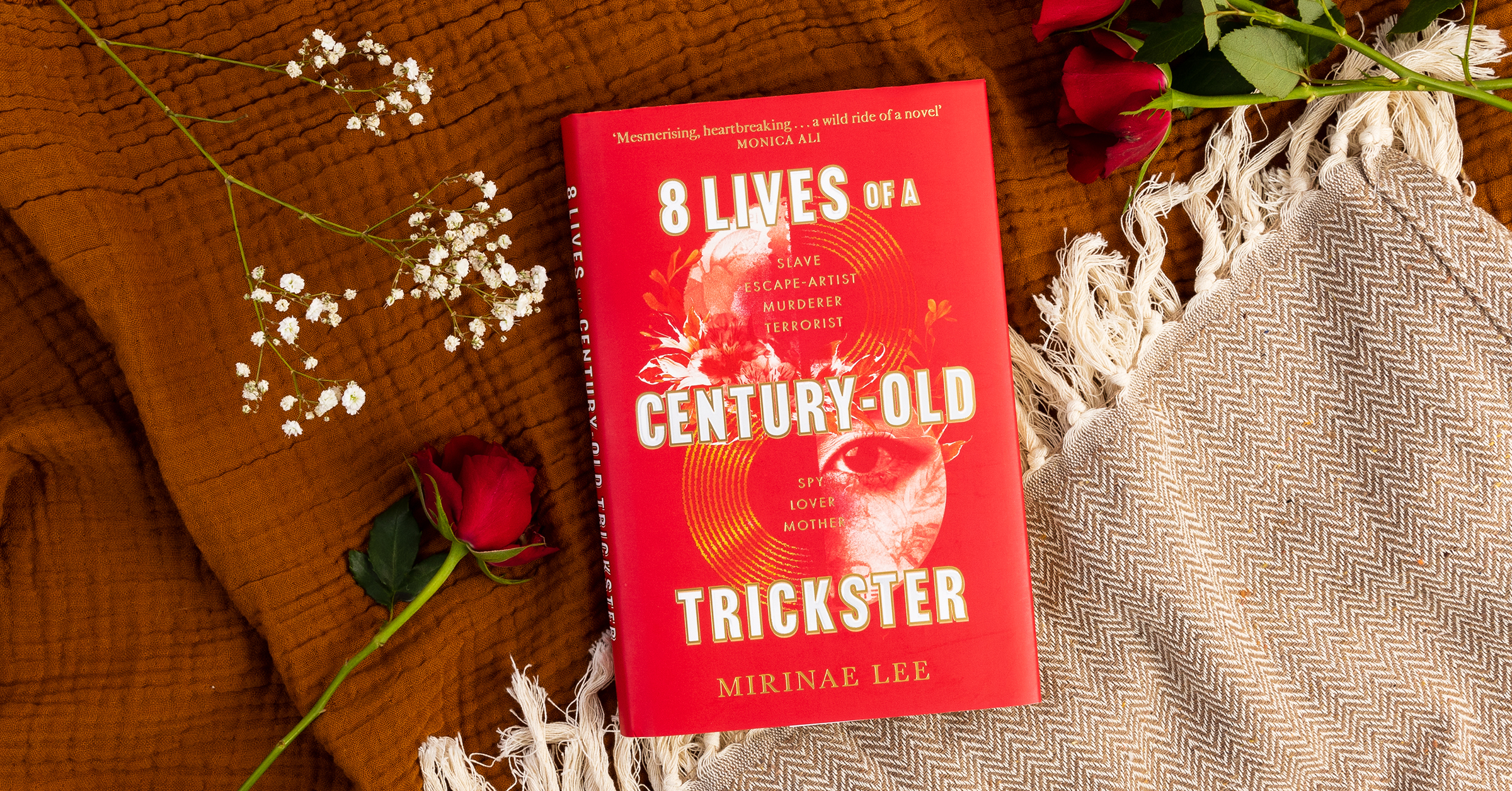

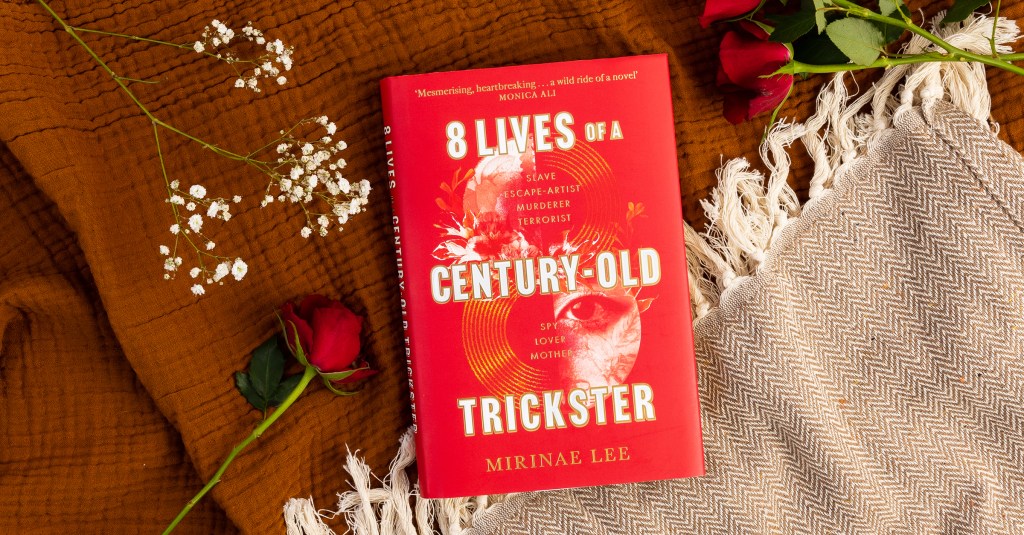

Read an extract from 8 Lives of a Century-Old Trickster by Mirinae Lee

‘Heartbreaking’ MONICA ALI

Prologue

The idea came to me while I was going through my divorce.

I was forty-seven and overweight. I had no child who would occupy my lone, silent days. I wasn’t one ofthose independent modern women who decided not to have babies early on. I wanted to have one but my husband couldn’t – due to his oligospermia, he told me. I wanted to try IVF treatment but he refused, saying the whole process felt too demeaning to him. I was furious later when I learned that he had already signed up to a famous fertility clinic in Gangnam with that new girl, twelve years his junior, amonth before our divorce was finalized. For weeks I had the occasional dream of ham- mering him to death. In reality, of course, I possessed neither the courage nor the penchant for violence to do it. Yet Idid imagine myself bursting into his office in Gwanghwamun, like an angry ajumma in Korean Morning Drama might do to attack her cheating husband, hands busy filling the air with leaflets that detail his treacherous deeds, all the while shouting the list of his sins in front of his coworkers, who would ostracize him for what he’d done. Of course I never executed this fantasy: submitting to such a hysterical course of action would be too demeaning to my dignity. Entertaining the thought of it, though, was quite thrilling.

I was desperately seeking a change in my life. I signed up for a gym and worked out for an hour three days a week. Although I began to lose weight and feel healthier, the physical change alone wasn’tenough for me. Ever since I was little I’ve been a pensive being, fond of reading and thinking and scribbling things down in my Moleskine. I needed more than just a fitter body. I needed a change that would engage my mind as well.

I was waiting for an appointment with my therapist and flipping through a women’s magazine when Isaw the article. It was the story of a hospice doctor in Singapore, who helped his dying patients organizetheir funerals and write their obituaries before their death. Contrary to common belief, the doctorexplained, many of his terminally ill patients weren’t that afraid of death: they were more concernedabout the aftermath, the posthumous grief and turmoil that their loved ones were to endure. His new program was met with a surprising degree of enthusiasm. Lots of patients reported they felt mentally andphysically better after they had participated in the arrangements for their passing. It gave them a senseof control and reassurance, and an invaluable opportunity to derive their own meaning from their shortjourneys on earth. I showed this article to Director Haam, my boss, and told her I wanted to launch a similar program for our patients. I couldn’t really complain about my job at the Golden Sunset: the salarywas pretty decent, the company guaranteed plenty of paid holidays, and my schedule and tasks were never taxing. What I mostly did was a mild version of accounting, but my official title was personal assistant to the director. Director Haam was a nice woman in her early fifties, a double-divorcee raisingher three kids with two different family names. She didn’t seem to possess much passion for her job at the Golden Sunset; she told me she’d chosen itmainly for its stability, which she needed badly as a single mother of three children. Director Haamtapped her desk nervously with her blood- red nails before she declared the Golden Sunset hadno funding for custom-made funeral preparations. I told her the obituary-writing program alone would be sufficient to make a change. Though reluctant, she gave me permission to start it after I promised her that it wouldn’t affect my performance of my primary duties, and that I would work extra hours if necessary. Before leaving the office, she threw me a worried look, as if she were thinking, I’ve been there, too. But instead she said: “Give me a call if you need a drinking buddy from time to time.” As Ilistened to the clicks of her heels fade away, I wondered if divorce would be any easier the second time around.

The obituary-writing program first helped me on a practical level. It diverted my attention from divorce. My thoughts, which until now had raced back to my husband and our fallen marriage again and again like a faithful dog, began to dwell on the lives of others.

“I’m here to help you write your obituary,” I told the elderly, in the most calming voice I could muster.“You can tell me a brief version of your life story, things that have made you happy, things that you’re proud of, and things you regret. How you want to be remembered by others, those who love you and care about you.” After taking a few deep breaths, most people began to open up quite naturally. Awareness of your limited time can bring a surprising degree of honesty to your speech, by shutting off the inconsequential background noises that would normally obfuscate your life. To the small number ofpeople who had difficulty starting their stories, I offered a simple prompt that always worked: “Pick three words – noun, adjective, verb, anything – that could define you or best describe your life.” Three is themagical number that people tend to fall for. A single word seems impossibly limiting, while two may feelunpalatable, as if they imply a double life. But three suggests a perfect balance, as in triumvirate and trilogy and trinity. People feel comfortable with it – neither too little nor too much.

Looking ahead to the end of their lives, people feel the urge to leave their footprints on this world, no matter how small they may be. And writing their obituaries confirms that their lives mattered – to them, and to the people for whom they had happily sacrificed their dreams. In the minds of youth, an obituary is a sad and solemn thing, but old folks understand that it means, among other thing, a privilege. Old folks, who are used to flipping through the pages of a newspaper, know that an official obituary is reserved for the deaths of house- hold names. Even the famous ones must fight constantly for ever-so-cramped space; most should be content with just a couple of lines, while a very lucky few get an entire para- graph. A whole page is, of course, impossible, unless you’re a high-profile politician, such as an ex-president, or an internationally influential warlord. At the Golden Sunset, however, every death meritsan entire page. That was the central idea of my project: Don’t we all deserve a full obituary of our lives? I wanted to believe that every death and life, even the most obscure and inconvenient ones, have important stories to tell. And I was there to lend my ears and pen to the final whistles of the tumbleweeds.

It was the second day of the Lunar New Year holiday when I met Ms Mook for the first time. I had volunteered to work since I wasn’t ready to face my first big family gathering after the divorce. I knew the kinds of questions I would get from my uncles and aunts, and especially my cousins, all of whom were still happily married with kids. I wasn’t ready for others to pick at my scabs yet.

A public nursing home might be the loneliest place on earth on a big national holiday. More than a thirdof the residents at Golden Sunset had no immediate families. A small number of fortunate people,those still in decent health and in touch with caring relatives, were invited out for a day or two. After thelucky few left the facility, a harrowing silence took over. The kind of quiet that put even the jumpiest dementia patients into a coma-like gloom.

That evening, in the lonely silence of my office, I received a call from the head caretaker of Section A. It houses nearly half of the senior citizens of Golden Sunset who have been diag- nosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Normally I didn’t have much business with that half of the facility because only the mentally competent and coherent can participate in the obituary-writing process. That day, however, many staff members were on leave so I was to help with whatever task was at hand.

I was asked to stand guard in front of a double room. Grandma Song Jae-soon had disappeared again, the head caretaker told me. My job was to wait and notify the other staff immediately if therunaway returned to her room while they searched every nook and cranny of Golden Sunset for her. Iwedged the door open with the small folding chair I’d brought from my office and sat down on it. Walkie-talkie in hand, I looked up and down the corridor, hoping for a sign of Grandma Song Jae-soon.

Then I saw a figure standing inside the room, her back leaning against the wall. A slender woman, covered with white from head to toe. I let out a muffled cry. “Don’t worry, I’m not a ghost,” murmured the figure, and laughed off-key. “You saw me earlier, remember?”

Her name was Mook Miran and she was a roommate of Grandma Song. I had indeed seen her when Ivisited her room. She’d been in her bed, slowly coming around from her late nap. I didn’t recognize her: she was quite tall standing up, but lying down she was indistinguishable from other silent and small-framed elderly bodies. “You’re the obituary woman, aren’t you?” She grinned, and color rushed to her face.

Mook Miran was a strange-looking woman with an equally strange name – it was my first time meeting a Korean with the last name Mook. She had big frizzy hair, which was entirely and evenly white, and it hung around her head like a halo. Her limbs were long and thin like a snow crab’s. Under the fluorescent light I felt I could read her body like a map. Veins showed through her translucent skin, like crisscrossed mountain paths, mostly mauve and pale blue. The bleaching light also drew a pair of butterfly-likeshadows under her high cheekbones.

“Yes, I’m the obituary woman,” I answered, still in awe of her.

“I’ve seen you out there in the cosmos garden, talking with the old ones,” said Ms Mook.

She called the other patients the old ones, as though she was different. And yet with her sharp eyes,and her memory of me, I wondered what she was doing in Section A.

“You should write my obituary,” she said, revealing a chipped front tooth.

I hid my bewilderment and told her we could have our talk right now if she didn’t mind, while we waited for the return of her roommate. I was surprised by the clarity of her mind, but I was still wary of her: I assumed that if the administration had decided to put her in the section for patients with Alzheimer’s, they must have had a good reason for it.

“Do you remember why you’re here in Section A?” I started, a little ruthless because I wanted to know if this was going to be worth my while. I didn’t want to come back to her the next week and be greeted with a flummoxed face shouting, Who the hell are you?

Ms Mook said she had been in the regular section at first but they’d moved her here about six monthsago, for a reason she never fully understood. “I would say my mind works normally, but it’s up to them todecide, isn’t it?” she whispered. Her cheeks twitched.

Still suspicious, I asked her the big first question. “Which three words would you choose to sum up your life?”

She walked back to her bed and sat down on it. Then she turned her head slowly toward a wall andstared at it. Her face was blank – as flat and pale as the whitewashed wall behind her. Mouth slack, eyes ashen. She’s blacking out, I thought, anticipating the inevitable: soon she would bring her gaze back to me and ask me who I was, what I was doing there.

Instead I heard a snort. “You genuinely believe a person can sum up her life in just three words?” shemurmured, eyes still fixed on the wall.

Her question caught me off guard but I feigned calm. After a moment of silence, I asked her how many words she would prefer.

“What would your three words be? Have you thought about that?”

Again she asked her question, ignoring mine.

I felt strangely tense. I felt as though Grandma Mook and I were suddenly engaging in a war of questions, and the one who answered first would be the loser. I summoned a wan smile, the gentle curving of eyes and lips with no teeth showing, the kind I usually wore to disarm incredulous grandpas. I was doing this partly because I couldn’t answer her last question. I had no idea what my three wordswould be. I’d never given it a thought, although I asked it of others all the time. And no one had asked me before.

“Ms Mook, do you want me to talk to the administration for you?” I asked her, holding on to my work smile,like a shield. I told her I could talk to the staff about her accommodation if she thought she was in the wrongplace. I said all the elderly residents I had helped with their obituaries were in the regular section. I knew this wasn’t a question she could easily ignore. “That’s not necessary,” she said casually, defying my assumption again. “I’m fine here in Section A. And there’s not much difference in the end, is there? In neither section are we allowed to walk out of the facility alone. Besides, although people in Section A get one hour less for the daily garden stroll, each room here has fewer people and thus more space.

Before, in the regular section, I shared a room with three other old women. Here, only one. So, moreprivacy.”

“But don’t you find it difficult to room with Grandma Song?” I’d heard this wasn’t the first time Ms Song Jae-soon had pulled off a stunt like this. The head caretaker told me her condition was getting worserapidly – she had, on occasion,

smeared feces on the wall.

I heard another snort – a gentler one this time.

“I volunteered to room with her,” said Ms Mook. Another answer I wasn’t expecting to hear.

“Why?”

“If you have some context from a person’s life, you can handle her better. Even if that person happens to be an Alzheimer’s patient.” She turned her head toward me to look me in the eye. “Did you know that both of Song’s parents were killed during the Japanese occupation?” she asked me.

I shook my head, wondering where this was leading. I clenched my jaw, the way I did unconsciously when I felt impatient.

Ms Mook said Grandma Song’s family had been rich landowners for generations. But overnight the Japanese had taken almost everything they owned – under a false pretext, for sure. “Such things happened all the time back then,” she added flatly. “Luckily her parents were warned by one of their neighbors, just a minute before the Japanese police burst in and ransacked the place. They didn’t have time to hide big objects, just small things.”

Ms Mook looked up at me, as if expecting me to take over and finish her statement. Clueless, I stared back at her.

“Grandma Song, with her little sisters, had to swallow as many jewels and rings as possible, as fast as they could. The police took all the valuables they could find and killed the parents on the spot, in front of the children. But Song had to move on, you know. No time to weep. She was the head of the family now. She had to spend the next few days rummaging through her own excrement as well as her little siblings’ to find the jewels. Their whole fortune now.”

Ms Mook sounded different. Her speech was now slow and halting. Her face was flushed, and a purple vein jumped in her thin neck.

She said Song Jae-soon at Golden Sunset, with Alzheimer’s playing her time backward, seemed stuck in this period of her childhood – the death of her parents and trying to support her little sisters. Ms Mook once noticed, when she saw Song engaging in fecal smearing again, that she mumbled names such as Jade, Pearl, and Ruby. The nursing assistants thought those were the nicknames of Song’syounger sisters. Ms Mook knew they were wrong.

“She wasn’t simply toying with her stool the way others with dementia do. She was going through herexcrement to find the jewels. In her mind, in her receding memory, Grandma Song is again the thirteen-year-old girl struggling to survive.”

Ms Mook stood up and walked to the wooden dresser in the back of the room. She squatted andopened carefully the silicon child-safety lock on the bottom drawer. Then she took out a round rustyFruity Drops can. She put it into my hand and gestured for me to open it.

Inside lay a dozen glitzy pieces of plastic jewelry.

“Those are toys for little kids. Too big to swallow,” said Ms Mook, picking up the heaviest piece that was shaped like an oval diamond. It shone gaudy pink, the image of Sailor Moon embossed on it. It was as big as an eyeball. “I put these in Grandma Song’s hands when I see her getting ready to examine her number two. I tell her we’ve already found the jewels. Then she’s happy, and stops immediately what she’s doing. No need to use force then. No needles and no drama.”

Speechless, I stared at the Sailor Moon on the jewel.

Then my eyes roamed toward the dresser behind Ms Mook, and found a stack of paper in the bottom drawer, still wide open. Next to it I saw a little mound of colorful bric-a-brac, which I couldn’t make out clearly from a distance. “What are those in the drawer?” I asked her.

For the first time Ms Mook seemed a little nervous. She walked quickly back to the drawer and closed it. “Nothing that’s forbidden,” she answered calmly, but a gleam of worry lingered in her eyes.

When I was about to repeat my question, the walkie-talkie on my lap brayed.

“Security has found Grandma Song,” the head caretaker yapped, through electric crackles, “She’s fallen asleep in the cleaning-supplies room, would you believe?”

From far away I heard hurried footsteps approaching, prob- ably carrying Ms Song back to her room.

I looked at Ms Mook. “Can I see you again?” I asked her.

*

I liked being in the cosmos garden even when all the flowers were gone. I loved being outdoors under thesun, away from the smell of Clorox and dried urine, which permeated every corner of the residents’ roomsand the corridors in the nursing home. Besides, the sun has a magical power: sometimes the despairgaping at my feet by night appeared too puny to bother me in the light of day.

Ms Mook, too, seemed different under the sun. It was a dry, windless afternoon. The sun was an ebullient eye in the middle of the acid-blue sky. Ms Mook appeared in a wheel- chair, pushed by Ms Docgo, the oldest nursing assistant in Section A. “You have one hour and a half before Grandma Mook’sbath time,” said Ms Docgo, bluntly, eyeing me and Ms Mook with muted hostility. She walked backto her building.

The sun was so piercing it made my eyes water. Ms Mook narrowed her eyes, made an arching sunshade of her hand and put it on her forehead. Squinting, her eyes covered with a rheumy film, she seemed as helpless and worn-out as most of the patients in Section A. Her hair and her bleached gown looked even whiter under the sun than under fluorescent light. Motionless, she was a plaster cast shaped like a human.

As soon as she opened her mouth and talked, however, she was a full presence.

“You can’t wait to write about me, can you?” she said, and lifted one corner of her mouth a little. Strangely, I saw a little boy in her old woman’s face.

“I couldn’t wait to hear what you have to say. I haven’t even thought about writing yet.” This was theplain truth.

Ms Mook seemed to be relishing the silence before she unspooled her story. These secondsseemed to suck all the air around her into her meager body. And as I listened to her talk, I wondered what exactly it was that lured me toward her words. It wasn’t obvious. Her talk was mostly slow and her voice always low. Still, she was the kind of person people naturally paid attention to, whose talk they rarely interrupted. The very antithesis of me. I wasn’t born with such charisma. I was a person who’s easily won over by others, according to my husband. Too easily impressed, and fooled.

And fooled was how I felt as our conversation progressed. Though fascinating, the introduction of her story was filled with elements far larger than life. When asked about her age, she said she would be “one hundred the day after tomorrow.” And yet she couldn’t have been that old. She looked at most eighty-seven. I’d seen my fair share of ancient people nearly a century old in Golden Sunset but none had ever sounded as acerbic or cheeky as she did.

I wasn’t sure what role I was supposed to play. Should I be angry at being taken for a fool who would believe such nonsense? Should I be level-headed, like an investigative journalist, trying to uncover logic in an illogical situation? Or should I be an eager spectator at this theater of the absurd? Reluctantly Iopted for the latter and kept listening, fighting my urge to interrogate her for facts.

She said she had had three nationalities in her life.

“I was born Japanese, lived as North Korean, and now am dying as South Korean.”

Her generation was born under Japanese colonial rule so technically she was born Japanese. But I couldn’t grasp lived as North Korean. I asked her if she had escaped to the South during the Korean War, and she told me she’d earned South Korean citizenship only after her hair had turned gray. “I spentmy youth in Pyongyang,” she added casually, as though Pyongyang was a normal part of the world anyone could visit whenever they liked.

Half of me cocked an eyebrow in doubt, but the other half nodded. The latter felt that this back story solved at least one mystery about Ms Mook: her accent. Though very faint, she had unique intonation that rose and fell in unexpected places, an accent that sounded blunt and sing-song at once. I wondered if it was a faded version of the Gangwon-do accent butI couldn’t quite place it.

“Japanese. North Korean. South Korean,” I repeated. “You already have your three key concepts foryour obituary. Don’t you think they represent your dramatic life pretty succinctly?” I forged a smile on my face.

“Why are you so obsessed with three concepts?” she asked, head tilted like a crow’s. “Is there some sacred meaning behind it?”

I shrugged my shoulders awkwardly and said no. “I find it practical, that’s all. One and two are too limiting,while, let’s say, nine is too bulky and therefore a turn-off. Three is just the perfect number for everyone to fill.”

Ms Mook turned abruptly to the side, like a pigeon bobbing its head away. Ha. It was a hybrid soundbetween laughter and a snort. She was now directly facing the honey-gold sunlight that was hitting the cosmos garden sideways. It made her squint again. “Eight, then,” she said.

“What?”

“Eight. I will give you eight words. Our middle ground. You said nine is too many and I say three is toofew. So eight. Take it as a sign that I respect your method, Ms Writer.”

She looked at me and winked. A wink that looked more like a twitch of an eyelid muscle.

“So what are your eight words, Ms Mook?” I asked her, noticing the cheeky one-sided smile return to her face.

“Slave. Escape-artist. Murderer. Terrorist. Spy. Lover.

And Mother.”

I sat in silence. I saw her eyes light up like a Christmas tree – she was elated that she’d floored me and was dying to hear my words.

“Those are seven words. Not eight,” I told her.

“So you really listened,” she said. Her cheeky smile grew wider.

She asked me which story I wanted to hear most and I said: “Murderer.”

That made her laugh. It surprised her, she said. I didn’t strike her as someone who would go straight to Murderer. She’d thought I would run first to either Lover or Mother.

I told her she’d gotten me wrong. “Who did you kill?” I asked her.

She clicked her tongue. “Not so fast,” she said.