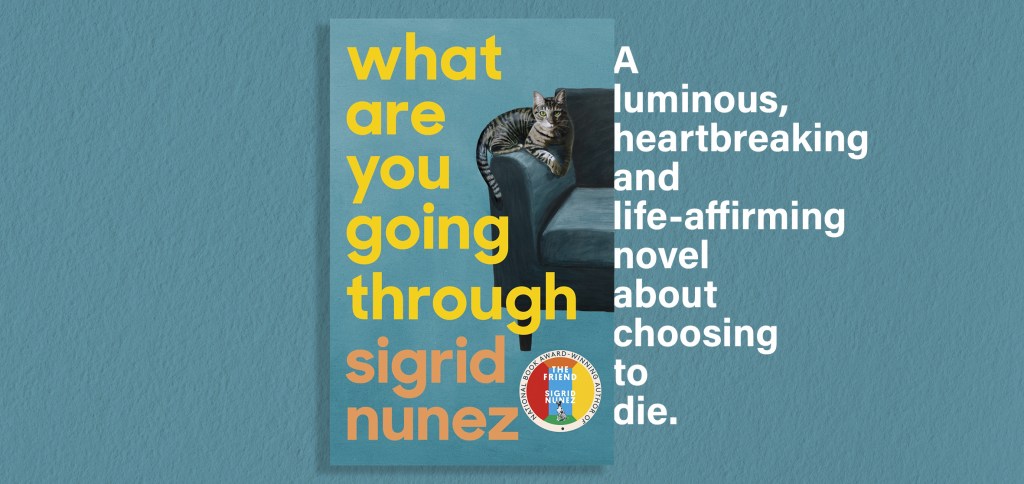

Read an extract from What Are You Going Through by Sigrid Nunez

Read an extract from What Are You Going Through, a luminous, heartbreaking and life-affirming novel by National Book Award winner and bestselling author of The Friend, Sigrid Nunez.

‘Love, death, friendship, compassion & SO MUCH wisdom. I just adore Sigrid Nunez’ Paula Hawkins

‘If the meaning of life is that it ends, Nunez gets to the nub of meaning in her brilliant novel. I loved it as much as The Friend’ Susie Steiner

‘I was totally overwhelmed by this extraordinary novel. Even if it weren’t about a subject dear to my heart I would be equally thrilled by its grace and profundity. Sentence by sentence it’s a total joy – and sometimes, much to my surprise, laugh-out-loud funny’ Deborah Moggach

It’s down to two places, she said. One was a summer house on an island off the southern Atlantic coast. It belonged to the family of a cousin of hers who wasn’t planning to use it till later in the season. She and this cousin had never known each other well, but when he first heard about her illness he was kind enough to offer it for a little getaway. She’d been there once, many years ago, for a wedding, and she remembered how beautiful the house and the beach were, but even this early in the season the island was likely to be full of tourists, she said, and it was not so easy to get to, and besides, she said, I don’t want to spend the last days of my life in a red state.

So she was leaning toward the other place, the New England home of a retired couple, former college professors who now spent most of their time traveling and used Airbnb to book short-term renters whenever possible to help finance their trips.

We could have it for a month, she told me over the phone. Not that I think I’ll need that much time.

Would I ever get used to this kind of talk? Even as I wondered what to do about my mail—let it pile up, have the post office forward it or hold it for me—I found it unthinkable to ask how long I should plan to be gone.

It’s not like I’ve picked a date, she said. Though, as I say, I am ready to go. You could even say I’m impatient to go, which comes partly from my having already given so much thought to dying but also from having reached the limits of what I think I can bear. But I don’t know what my body will do.

Though she’d been feeling much better since she went off chemo, her symptoms could change from day to day, and the meds she was taking to suppress them had some side effects too.

In any case, I want things to happen naturally, she said. I feel like I’ll know when it’s time.

But you—well, you won’t know, she said. Obviously I won’t be making a big announcement. Like the coming of the Lord, she said jokingly: You will not know the day or hour.

She had decided not to tell anyone about our plans. I’ve come this far, I don’t want to risk some stupid intervention, she said, or even a tiny disruption. I want peace.

No one was to know where we were.

And, for your own protection, she told me, you need to play dumb: I never told you what I was going to do, you weren’t even aware that I had the drug.

I had, in fact, already told one other person everything, but I did not say this.

A photo of the colonial-style house had brought to mind the house where she’d grown up. They were both built in the 1880s, she said, though this one’s smaller. She told me how heartbroken she’d been about selling her childhood home. But after her parents died, neither she nor her daughter saw themselves ever living in such a big house in what had by then unfortunately become an overdeveloped suburb. Among other things that she liked about the retirees’ house, she said, was that it had been renovated with the needs of the aging in mind. There was a large bedroom on the ground floor with its own bathroom in which grab bars and a built-in shower seat had been installed. Given how frail she was now and how, some days, she had trouble walking, this was a lucky thing, she said. Also, the original master bedroom, on the second floor, was at the opposite end of the house. So we’ll each have our privacy, she said. (What I would do with all that privacy was, for me, a very big and daunting question.)

The neighboring houses were spaced well apart and one side of the property bordered a nature preserve.

I don’t know the town well, but I have passed through it, she said. I’ve always been fond of New England coastal towns. And I like that there are supposed to be some good restaurants, now that I’ve started being able to enjoy food again.

In fact, she didn’t really need to give it any more thought. This place looks perfect, she said.

Such excitement in her voice—anyone would have thought we were planning a vacation.

I’m sending you photos, she said, and shortly after we hung up they arrived. Half a dozen shots of the house, inside and out. One of the yard at autumn’s red-and-gold peak, another in pristine snow. I stared at them in a kind of stupor. I did not care what house, what town we were in. How much she cared was almost unbearably poignant to me.

She had just a few more things to do at home, she said. A few more drawers to empty, a bit more paperwork, some people to see one last time.

A week had passed since we met in the bar.

Start packing, she texted.

I was mechanically layering clothes in a suitcase when she texted again: Thank you for doing this. When I had told her the answer was yes, that I would do whatever she needed me to do to help her die, her relief had been so great that she began sobbing.

Seconds later, she texted again: I promise to make it as much fun as possible.