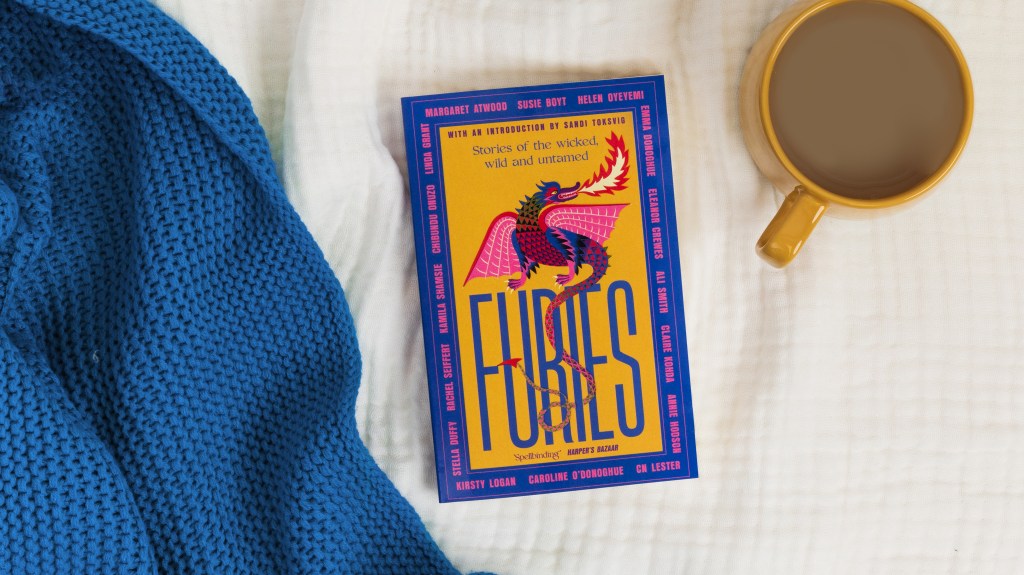

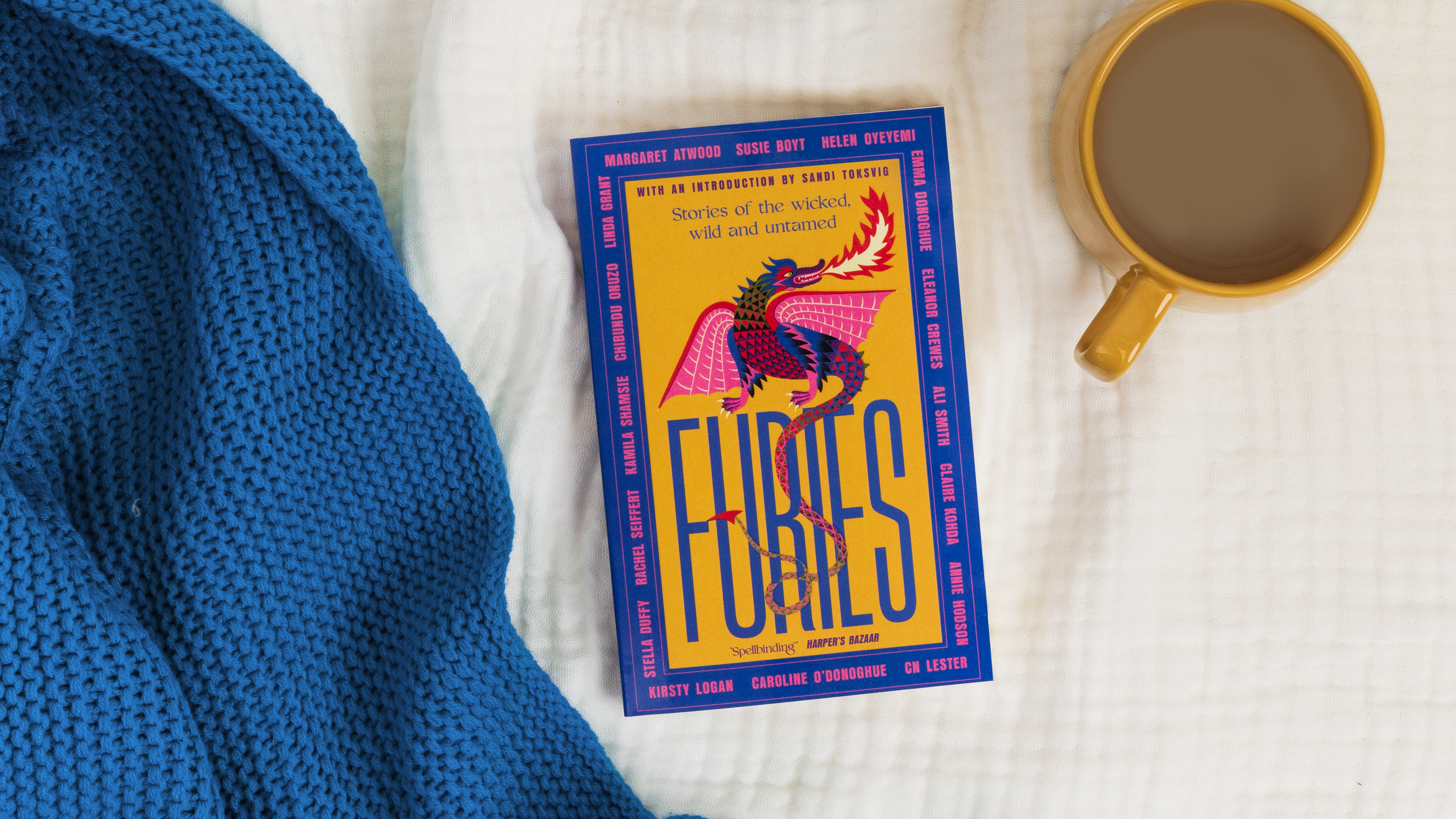

An extract from Furies: Stories of the Wild, Wicked and Untamed

BANSHEE. DRAGON. TYGRESS. SHE-DEVIL. HUSSY. SIREN. WENCH. HARRIDAN. MUCKRAKER. SPITFIRE. VITUPERATOR. CHURAIL. TERMAGANT. FURY. WARRIOR. VIRAGO.

An acclaimed, fun and fearless anthology of feminist tales, by sixteen bestselling, award-winning writers,

For centuries past, and all across the world, there are words that have defined and decried us. Words that raise our hackles, fire up our blood; words that tell a story. In this blazing cauldron of a book, sixteen bestselling, award-winning writers have taken up their pens and reclaimed these words, creating an entertaining and irresistible collection of feminist tales for our time.

Read on for an extract from Banshee by Annie Hodson

Rumour had it that someone in Ballytullan was marked for death. Whispers buzzed through the school assembly that the banshee’s cry had been heard the last three nights, and some unlucky person must be on their way out. Aisling listened with a thrill of fear. What if it came for Mam? What if it came for her?

At lunchtime the girls in her class huddled around the radiator and swapped stories, starting with the fact that old Jim Kelly had supposedly taken his shotgun and gone to find the source of the screaming last night.

‘It’s all nonsense,’ Anne Moore said. ‘It’s just the sound the foxes make when they have sex.’

Several girls giggled at the word sex, but Roisin Barry looked mutinous.

‘It’s not nonsense. Mrs O’Connell saw her out the window, I heard her telling my auntie.’

A clamour went up for Roisin to describe the banshee.

‘She was sitting in the tree opposite the post office. And she was wailing.’

‘Keening,’ Anne said. ‘Banshees keen, they don’t wail.’

‘What did she look like?’

Roisin wasn’t sure.

‘They’re either really young and pretty, or really old and ugly and scary,’ Claire Walsh said. ‘And they have all this long hair they comb, and if you steal their comb they’ll come for it in the middle of the night, and you have to hold it out to them with tongs or they’ll tear your arm off.’

Aisling shuddered involuntarily.

‘She must be here to kill someone,’ Claire said with satisfaction and Anne scoffed.

‘They don’t kill people. They just warn you that someone’s going to die. Or they would if they were real, which they’re not.’

The bell rang and they scattered back to their seats. Aisling clenched her fists in her lap and thought of all she knew about banshees. She’d heard of the combs before, although she’d always thought that was just something her grandmother said to keep her from picking dirty ones off the ground. And she knew what keening was. Irish was her favourite subject and Mr Ó Cearrnaigh had hammered into them the words the English had shamelessly stolen from them, like whiskey and galore and smithereens. But keening was the best of the bunch.

Chaoin sí – she keened. Tá sí ag caoineadh – she is keening. Caoineann an bhean – the woman keens.

In the examples in the Irish textbooks, the boys were always playing and building and taking. The girls were always feeling things.

Back home, Aisling broached the subject.

‘Mam, everyone at school’s saying there’s a banshee on the loose.’

Mam looked over from peeling carrots, brow creased.

‘What’s that, love? What’s on the loose?’

Mam couldn’t hear very well any more. The doctor in the city had given her hearing aids but Da wouldn’t let her use them. He said he’d be ashamed to be seen out with a woman her age wearing them, and that she needed to try harder.

The hearing aids went in a drawer and Aisling had to repeat herself two or three times for Mam to understand.

‘A banshee,’ she said slowly and clearly.

Mam laughed.

‘Sure, what would a banshee be doing in Ballytullan? Too small for the likes of them.’

‘Jim Kelly went out looking for her with his shotgun,’ Aisling said, moving to stand next to Mam so she could hear better.

‘Mr Kelly doesn’t have a shotgun,’ Mam said. ‘And he likes his sleep too much to be prowling around at night.’

Aisling felt comforted.

‘Really? But Roisin says Mrs O’Connell saw the banshee out the window.’

She didn’t notice her father at the door until he snorted.

‘That old bitch is the only banshee round here.’

Mrs O’Connell always used to invite them over for tea, and once she’d slipped Mam a note at Mass. Aisling never found out what it said, but she thinks her father did, because after that they weren’t allowed to talk to Mrs O’Connell any more. Aisling wanted to tell her father about Jim Kelly, but he’d already left the kitchen. She was hoping she might hear him laugh, his laugh that made everyone feel like they were in on the joke. She couldn’t remember the last time he’d laughed like that.

The next day at school, the class confronted Mr Ó Cearrnaigh on the subject of banshees.

‘Bean sí,’ he said, writing it on the whiteboard with a squeaky marker pen. ‘From the Old Irish ben síde. That was before colonisation and Anglicisation, of course—’

‘Bean means woman,’ Anne interrupted, always eager to be first to an answer. ‘And sí means fairy.’

Mr Ó Cearrnaigh held up a finger.

‘Sí means fairy now. It used to mean something like fairy mound. The mounds were where the fairies lived, and the banshee was one of them.’

‘That’s why they’re always angry,’ Claire said triumphantly.

‘Who wants to live in a mound?’

‘You better watch what you say or they’ll come get you, Claire,’ one of the boys at the back of the class said.

‘She’s not here for me,’ Claire said and Aisling wanted to ask what made her so sure. How could anyone know if the

banshee was coming for them?

‘What’s that?’ Mr Ó Cearrnaigh said and the class told him about the banshee’s visitation.

‘You girls have very active imaginations,’ he said jovially.

‘Less talk and more listening for the rest of class I think.’

Tá sé ag caint – he is talking. Tá sí ag éisteacht – she is listening. Labhraíonn na buachaillí agus éisteann na cailíní – the

boys speak and the girls listen.

Aisling looked up banshees on the school computer. She had to click away from all the horrible pictures, but she found some articles to read.

The consensus was that Anne had been right, banshees didn’t kill anyone. They only foretold death. They didn’t cause it.

That was some comfort to Aisling, although none of the websites told her how to find out whose death they were foretelling. The people in the stories were usually sick already. She didn’t know any sick people in Ballytullan, except maybe Muireann’s poor sister, being treated for cancer in the city. But then the banshee would go to the city, wouldn’t it? Not come here?

All of the articles spoke of the banshee’s lament, keening for the one lost. But a few said that the banshee’s cry could be one of victory too. Sometimes the one marked for death was a wicked person. An evil-doer. The banshee would rejoice over them as one would rejoice over the slaughter of an enemy. Aisling didn’t know any wicked people either. Except—

When she got home that night, Mam was crouched on the kitchen floor, picking up shards of broken glass. The room smelt like whiskey, hot and harsh. Aisling brought over the dustpan and brush. Mam had a new bruise on her cheek.

Aisling woke just past midnight. A sound was drifting through the air towards her. It was neither a scream nor a wail, but a song. Soft and sad and for her ears only. She got up and dressed in the darkness. Pulled on her coat and scarf and gloves and padded out of the back door. She followed the song through the gate, across the field, and all the way to the hazel tree by the crossroads.

Beneath the tree, the banshee stood.

She was neither young and beautiful, nor old and terrifying. She looked to be about sixty, sensibly dressed in a raincoat, thick boots and a woollen hat. Her long grey hair hung to her waist and there was something gleaming white in her pocket. Her lips were parted in song, and it was no louder now than it had been in Aisling’s bedroom. Aisling wasn’t afraid. She couldn’t be, somehow, now they were face to face. Not with the banshee looking like that, so oddly familiar and reassuring, like the women who worked in the post office or the café or the library, sturdy and solid and kind. The ones who discreetly pressed money into Mam’s hands or murmured that they’d always have a place for her to stay, should she need one.

The song ended but the banshee didn’t leave.

Aisling inched a little nearer. Her mouth felt too dry to talk but she didn’t think the banshee would speak either. Could she only keen? Or if she spoke, would it be in a language that time had long forgotten? They didn’t need words. Aisling raised one shaking hand and pointed across the field to their little house, set alone at the edge of the town.

The banshee nodded and Aisling knew she understood. Then she crooked her finger for Aisling to come closer.

The banshee delved into her pocket and drew out the gleaming thing. It was a comb and she held it out to Aisling.

It was big, so big that Aisling had to hold it with two hands, each tooth sharp and bone-white, like they’d been freshly bleached.

Aisling nodded. She also understood.

Annie Hodson is a queer writer and playwright from York, and one of the 40-strong cohort of the London Library’s 2022-2023 emerging writers’ programme. She won the Virago short story competition, with her story ‘Banshee’, which appears in the paperback of Furies.