The Tea Towel by Melatu Uche Okorie

My Wrappa of Irish Literary Female Writers

My publishers sent me a piece from the Irish Times by John Boyne on the Irish literary tea towel in which he highlighted the absence of female writers on the old literary tea towel. They wondered if I would be interested in doing something in the same vein – write a piece on writers that I would ideally have on my own Irish tea towel if I were to create one. Creating a literary tea towel of my favourite Irish female writers seemed a simple enough task, seeing that Ireland has a lot of great female authors. My head was soon swamped with possible names, and I spent many days in an excited frenzy, picking up and leafing through novels, rereading marked lines or folded pages or half-chapters of books that had enthralled me, re-admiring the way a writer had captured a thought or an emotion on a page.

But the phrase, literary tea towel did not feel me. I wanted something more – African. I decided that mine would be a Wrappa of Irish literary female writers, being that the wrappa is one of the most essential pieces of clothing in most African homes. The design on my wrappa will resemble that of the Catholic Women’s Organisation’s wrappas while growing up, which used to have the image of the Pope in different poses imprinted all over it. The type of wrappa would not matter – whether it’s Ankara (produced in the West African countries), Hollandis (made in Holland) or the Indian George (named after one of the King Georges); all of that will be inconsequential. The focal point would simply be the motif, and just like signature quilts that are covered with patchworks of family logos and crests, my wrappa would have the faces of my favourite Irish literary female writers adorned on it.

Because our days are never still but in actual fact are often filled with events, and when nothing of import happens – there are decisions to be made (no matter how insignificant), my mind, as time went by, not only churned out and refuted names of Irish female writers but I also realised that I was mentally dividing them into two possible groups: the Irish female writers that I admire, have read and enjoyed their work since coming to Ireland, and the Irish female writers whose books, long after I had finished them, not only played on my mind but were used as anecdotes in conversations, as they had influenced my view of a situation. For the latter, I have only three! I could boost up the number by throwing in one or two of the writers that I had thoroughly liked their novels, but I wanted a wrappa of writers that had much more than great reviews. I wanted it to be about risk-taking and honesty in storytelling to the extent that may have made the writer unpopular. I wanted it to be about authors who unabashedly bared their souls in their narrations; those who did not choose a safe path in their depiction of Ireland, something I am sure not many would do without compromising in one way or another.

The first author on my wrappa of Irish female writers is Nuala O’Faolain. I read Nuala many years ago, and never have I seen a woman lay herself so bare. One cannot reach the end of Nuala’s autobiography, Are You Somebody? Accidental Memoir of a Dublin Woman without feeling a strong sense of awe for her. For how many people would dare to reveal their life follies, or be audacious enough to expose their loneliness to the world? In Are You Somebody?, Nuala fearlessly threw open the hidden world of the lonely that many writers have used characters to depict in a bid for self-preservation. She wrote of sex in ways that could make a grown woman blush. Not because she was explicit and excessive in her descriptions, but rather the reader’s unease stems from being conversant with some of Nuala’s critical and oftentimes harsh description of her feelings during such engagements. Her self-analyses are familiar, which also makes one to be nervous, uncomfortable and sometimes, embarrassed. I pondered in awe as to whether there was a recklessness to Nuala, for how could she be so unafraid of being shamed?, boldly divulging her need to be loved even if in the arms of the wrong men, freely admitting to the self-doubts that we as humans dragged around us everywhere but do our utmost to hide? So, by the time I read Nuala’s second book, a novel titled My Dream of You, I had become desperate to set eyes on her. I was saddened to find out she had passed on, and so I sought out the few interviews she had granted before her death, committing most of her responses to heart. It was in her interviews that she revealed the repercussions that came from writing her books, how she was made fun of and dismissed as a woman who was going through a mid-life crisis; and her resolute view of Ireland as a country that was unkind to women. In reading and learning about Nuala, I was never once in doubt as to her inner strength, even though something about her brought on feelings of protectiveness. Her unflinching honesty towards herself is admirable, and it will take time before any autobiography would ever compare itself to Are You Somebody? in my eyes for not many authors (I include myself here) could hold his or herself up to such inflexible scrutiny.

The central reason for having Anna Burns on my wrappa of Irish female writers is simply because of the effect Milkman had on me. Anyone who has chosen to make Ireland their home dismisses this book is at his or her own peril. Milkman is a gift from Anna, and it offers a profound insight into the psychological mindset of a people. Although set in Northern Ireland of the 1970s, everything about the story is still relevant today. I held Milkman in my hands, transfixed in the same position I was seated while reading the last pages, conscious of the passage of time but too overcome by the feelings the book had risen in me to care; for Anna had articulated so beautifully perplexing cultural conducts that persons new to Ireland occasionally grapple with. It’s a tale about an un-based and un-founded accusation, something that those who have experienced it would forever remember the sting of. Anna excelled herself in her laying bare the reasoning of a people at a particular time, the result of which is a deconstruction and de-mythification of the age-old adage, ‘There’s no smoke without fire’. For if there is a propensity for exaggeration, two plus two could readily add up to four hundred and forty-four again and again…as a local saying goes, ‘Never let the truth get in the way of a great story’.

The last writer on the wrappa of Irish female writers is Edna O’Brien. In a way, Edna made it onto my motif by default – I knew of Edna O’Brien as a writer but had never read any of her books until the Dublin One City One Book when I found about the ‘evil literature’. The mere idea a book being banned and then celebrated piqued my interest. Wasn’t there something very Irish about that? First, a unanimous condemnation, and then years later, in an attempt to make right when nearly all the injured parties are long dead or past caring, there is a resuscitation of the same thing and a unanimous condemnation of it having been condemned in the first place! In this case though, I was glad for Edna that she was still alive to witness the vindication of her creative imaginations, for that was all it was in the first place. And so, I borrowed some of Edna’s novels from the library, and scoured interviews with her, curious to know how she felt at the time and how she got through it. It wouldn’t have been easy to live through a country’s burning of one’s creativity.

In reading Edna’s work, I discovered an author who was close to the landscapes of her childhood and used it as a fodder for her stories. Each of her tales was a reminiscence, even though she had described the country in her story, A Scandalous Woman, as a land of shame, a land of murder and a land of strange, throttled and sacrificial women. In her interviews she spoke about being ostracized after The Country Girls, describing walking down streets and having doors closed at the sighting of her, and the decision to leave Ireland – a case of leaving in order to live. While the character in Anna’s Milkman used silence as a tool for surviving her environment, Edna resorted to turning her back on the country where she was born. Reading Edna and listening to her interviews made me realise that Edna’s real-life was quite akin to the imaginary ones she created on paper, a true case of life resembling art or better still, life being art.

For now, I have just three Irish female authors imprinted on my wrappa of literary writers, but I am excited, as I read more Irish authors, at the prospect of having more names and faces adorned on my wrappa. And, the same way wrappas come in different designs and colours, so do I want imprinted on my wrappa different kinds of faces of Irish writers that has impacted my life – writers from Irish black and ethnic minority groups and Irish male writers.

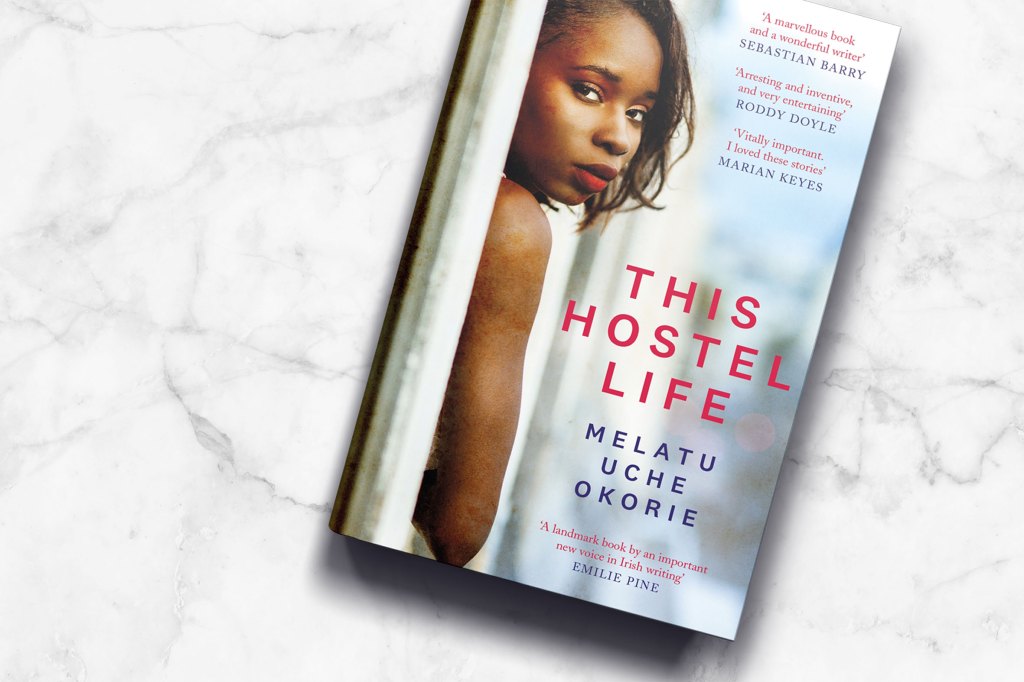

Melatu Uche Okorie’s own short story collection, This Hostel Life, is out now.

SHORTLISTED FOR THE AN POST IRISH BOOK AWARDS SUNDAY INDEPENDENT NEWCOMER OF THE YEAR

'A landmark book by an important new voice in Irish writing' EMILIE PINE

THIS HOSTEL LIFE tells the stories of migrant women in a hidden Ireland.

Queuing for basic supplies in an Irish direct provision hostel, a group of women squabble and mistrust each other, learning what they can of the world from conversations about reality television and Shakespeare. In another story, a student shares her work with a class only to be critiqued about her own lived experience, and a mother of young twins, living in Nigeria, is at risk of losing her newborns to ancient superstitious beliefs.

An essay by Liam Thornton (UCD School of Law) is also included, explaining the Irish legal position in relation to asylum seekers and direct provision.

'Fresh, devastating stories . . . Okorie writes with uncomfortable clarity about things we think we already know' LIA MILLS

'Melatu Uche Okorie has important things to say - and she does it quite brilliantly' RODDY DOYLE