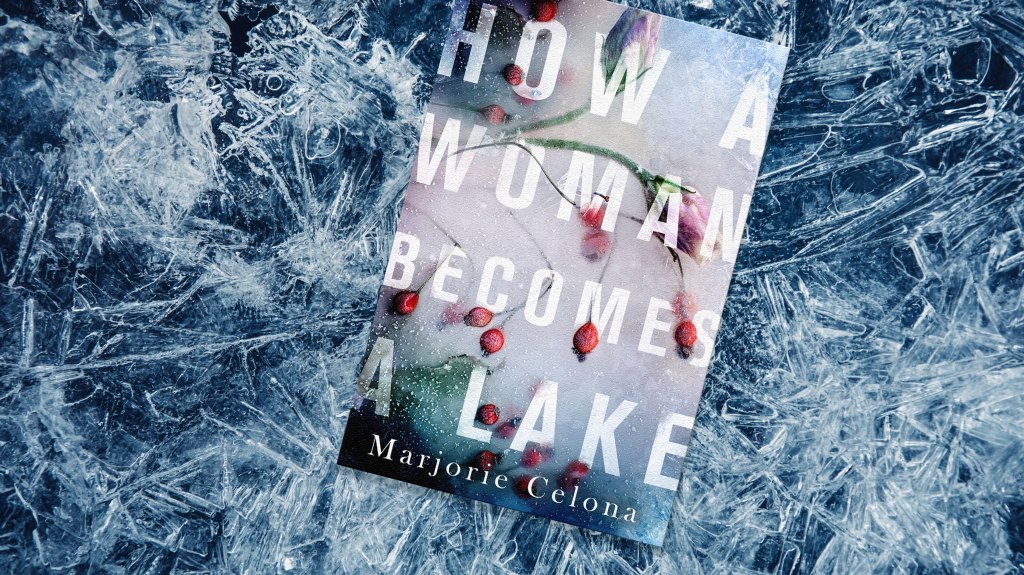

How a Woman Becomes a Lake by Marjorie Celona

Extract

How a Woman Becomes a Lake by Marjorie Celona

A compelling literary mystery about the dark corners in a small community, from Marjorie Celona, whose award-winning debut novel Y was praised by Evie Wyld as ‘a beautiful, moving book that explores what it takes to belong’.

Jesse

The paper boats were difficult to make, and Jesse’s hands were clumsy from the cold. It was New Year’s Day, and his father had brought him and his brother to Squire Point. They were supposed to write their wishes for the New Year on the paper boats, then set them on the surface of the frozen lake and wait for spring. When the ice melted, their father said, their wishes would come true.

Jesse was ten, and Dmitri, six. They sat in the back seat of their father’s car with the heat on high, each with a sheet of pale blue paper and a black felt pen. Theirs was the only car in the parking lot. Their father told them that most people preferred to go to malls. They had gone to the mall once, but the crying babies had upset their father and he had been short with his sons, annoyed. What was there to do with your children when you didn’t live with them anymore? And, so, they drove around.

On these long drives, they listened to the marine forecast. Their father had a transistor radio that bleated small-craft advisories, swells, wind waves, and knots. It was always on, though their father hadn’t gone sailing in years. Something he had done in a previous life—that was how he put it—when he still lived in San Garcia, a two-days’ drive away.

Their father had driven them out to Squire Point slowly, the roads unplowed. The car hit a pothole and their father swore. The Pineapple Express, their father said, and Jesse thought he was talking nonsense again. Their father talked of spiritual things sometimes—the universe and reincarnation; ghosts, spirits, telepathy—and he began to do so now. Squire Point was a magical place, their father said, a sacred place. It wasn’t all crazy talk, like their mother, Evelina, said. Jesse felt that Squire Point was indeed sacred; he felt it in his bones. He knew Dmitri would feel it soon, too. You had to be old enough to feel things like that.

They pulled onto the highway and their father told the boys about his old days in San Garcia, about his new girlfriend, and about his ex-girlfriends, an impressive list. He farted. He farted again and again. He sang and they made up songs. He hollered at a woman in a bus shelter, called her “chicky-poo.” He lit a cigarette but did not roll the window down. He didn’t wear a seat belt, though the boys were buckled in tight. It seemed to Jesse that it was a very long drive out to Squire Point, but time slowed when he was with his father— whether because he savoured the few afternoons they spent together, or dreaded them, he couldn’t tell.

Their father’s name was Leo, short for Galileo, though hardly anyone knew that. He was muscular, though too thin, with a curved neck like a heron’s and a big nose. Jesse knew he looked like his father—olive skin, so dark in summer it was almost black; the same dark hair; that same nose. Remarkable was the word people used—it’s remarkable how much you look like your father, they said. At first glance his father was a handsome man. The closer Jesse looked at his father, though, the less handsome he became. His eyes darkened when he drank: glassy and black, sunken into his face. He’d been born with a club foot and it had been corrected with surgery, but an ugly scar ran across his ankle that to Jesse looked like the face of a monster. His left foot and leg were smaller than his right—another thing hardly anyone knew. Who would notice such a thing? Most people didn’t notice much—even at ten, Jesse knew that to be true.

But Jesse noticed everything. His father kept a little bottle of tequila in the glove compartment and a slice of lemon in a plastic bag, smoked hand-rolled cigarettes from butts he’d picked off the ground. Their mother had kicked him out six months ago. Before he left, they all lived in an old house with a giant monkey-puzzle tree in the front yard. Now the boys lived with their mother in a small white beach house, and their father lived in a one-room apartment in what was said to be the seedy part of town. He slept on a foam mattress, with a travel pillow and a navy-blue sleeping bag, an extra blanket wadded in the closet for the boys. Nothing on the walls. A suitcase in the corner. No washer or dryer. A red toothbrush beside the kitchen sink. Nothing in the fridge except a half-empty bottle of wine. Jesse sensed that other people didn’t live this way. His father’s clean-shaven face, the medicinal smell of his aftershave, the specks of blood on his chin stopped up with toilet paper. The sight of him, the sound of his voice, made Jesse feel as if his whole body might shatter. Every time he’d seen his father these past six months—once a week was their current arrangement— his mother asked whether he’d had a nice time. He understood that he had to say yes. He knew, on some primal level, that it was better to have a bit of a father than no father at all.

Besides, his father was smiling and telling Dmitri a joke about a football-playing centipede. He pulled into the first parking lot at Squire Point, reached into his jacket, downed a can of beer in three gulps, then threw the empty can out the window and into the snow. “So the coach says to the centipede,” his father said, “‘Where were you during the first half?’” Jesse watched his father glance at Dmitri, pause, pause some more, then, when the silence had become almost unbearable, his father erupted: “And the centipede says, ‘I was putting on my shoes!’”

He seemed to be in a good mood. He told his sons that after they made the paper boats, he would let them shoot his rifle. They were not to tell their mother this, though they could—they should—tell her about the paper boats.

“You hear me?” he said, and Jesse nodded, remembering not to act too excited—their father was easily irritated, and the day could darken. That was the problem with his father, his mother had told him—he was neither good nor bad, but rather half of one and half of the other.

Outside the fogged-up windows of the car, the spindly birch trees, encased in ice, looked as though they were made of glass. Jesse wrote his wish on one side of the paper, turned it over, folded it, made a crease, and brought the edges together to form a V. The next part was difficult, and his father spoke in a slow, loud voice, holding up his piece of paper to demonstrate how, with the right folds, it could become a little hat that could then be flattened into a diamond.

Dmitri looked bewildered, and Jesse’s fingers shook, but soon the diamonds became little triangles, and then even smaller hats, and when the boys pinched the edges of their pieces of paper and pulled them apart, two small blue boats emerged in their hands.

“Put a penny in the bottom to weigh it down,” their father said, and passed each of his sons a coin. “Helps the wishes come true.”

Last weekend, Jesse had met his father’s new girlfriend. She was shorter than his mother, as thin and muscular as a dancer. Her name was Holly, and she had wild blond hair and wore no makeup. She answered the door in a long white gauzy dress, black leggings, and beat-up running shoes without socks. On the drive over, his father told the boys that she ran a harbourfront art gallery, with a studio in the back where she slept and an easel for her own work.

Jesse could tell she was pretty, but like his father, she seemed off. For instance, her studio had no bathroom or kitchen. She kept a bucket in the closet with a roll of toilet paper beside it, and in the same closet she stored cereal, peanut butter, soup cans, a hot plate, and a camping stove. When they had first arrived, their father presented her with, as he put it, a “windfall”: three half-used rolls of toilet paper, a tube of toothpaste, a large bag of beef jerky, and a bottle of multivitamins. Then, of course, out came the cans of beer.

She was an artist, sold her greeting cards and calendars to tourists. His father said the word artist with some reverence. Jesse thought the greeting cards were dumb. Watercolour paintings of flowers and fishing boats, so boring. Why not take a picture? Still, his father seemed lighter in her presence, and Jesse felt a tinge of guilt for he realized that he, too, was having a good time. Holly told him and Dmitri to look up, and when they did, they saw that the ceiling was covered in hundreds of origami birds. She put on some kind of tribal music and danced with her arms over her head. Jesse saw that she did not shave her underarms. It was thrilling to see the wild tufts of dark hair, as thick as his father’s, sprouting from those bone-thin white arms.

“Let me draw your boy,” she said. She stood behind a butcher-block table and sketched Jesse, then handed him a piece of paper with a charcoal portrait of his face. He could see his father beaming at this gesture, this bond between them. It was flattering to be drawn, and Jesse blushed.

When he got home, he hid the drawing under his bed where his mother would never think of looking. But she must have seen the piece of heavy construction paper while she was vacuuming. She presented him with it the next day: a charcoal rendition of his big eyes and sunken cheeks, his look of alarm, his bangs parted evenly down the centre of his forehead.

“He shouldn’t make you spend time with his girlfriends,” she said. Her tone was sharp, like when Dmitri was first born and she would get so frustrated that she would stop the car, reach over Jesse’s body, unbuckle his seat belt, push open the car door, push him out.

After his mother went into her bedroom for the night, Jesse climbed into Dmitri’s bed and fell asleep with his hand on his brother’s back. He watched his brother’s little sleeping body breathe in and out beside him. He had torn the drawing into pieces to show his mother that it meant nothing.

It was Jesse’s idea to run back onto the lake and steal a look at his father’s wish. His father had left his cigarettes in the car and was stomping away from the boys, calling over his shoulder at them to stay on the trail.

Jesse wondered what he wanted his father’s paper boat to say: I want to come back. I miss Jesse. I miss my family. Once his father was out of sight, he grabbed Dmitri by the hand, told him to be quiet, and the two of them sprinted to the edge of the lake, then inched out carefully, testing each step to make sure the ice could support their weight. The lake was covered in a fine layer of snow, and they held each other’s hands tight. Jesse figured he had about five minutes before his father returned.

He thought that a frozen lake would look something like a mirror, and that when he looked down, he would see his reflection. But the ice beneath his feet was covered in snow, and there was nothing to see within it.

Dmitri saw the bear tracks first and pointed at the imprint. They were only a few feet out on the lake and the tracks were hard to make out, could even be a big dog’s. The bear had come out about ten feet onto the lake, then circled back. Jesse told Dmitri not to worry, for already his brother’s face was breaking into a cry, and if his father returned and found his youngest son upset, Jesse knew he would be punished; it didn’t matter why or what had happened. His father got angry. He got so angry Jesse thought he was going to kill them, smash every glass in the house and bust out every window with his fist and kick over the chairs and pound the table with a hammer until it crashed into a million pieces on the floor. He’d be looking at the coffee pot and the next minute it was being whipped across the room, not for any reason, even when everything else was right—bills paid, waffles on the table, the radio on. The night their mother kicked him out, he got so angry he ripped out a handful of her hair.

Jesse’s hands began to shake from the memory, and he tried to figure out how long it had been since his father had left to get his cigarettes. Two, three minutes? Not long. But for how long had he looked at the bear tracks? Jesse pinched Dmitri’s arm and told him to shut up—“Shut up, you wimp!”—and pushed his brother ahead of him. “Get going,” he said. “Dad will be back soon. Hurry up, let’s go.” A few puddles had formed in the snow ahead of them but Jesse continued, his hand gripping the back of his brother’s coat for stability. Neither boy was dressed right. The wind ran through Jesse’s jacket and he felt the ice through the soles of his rubber boots. He wished he had on another pair of socks. He wished that he were home with his mother, that he was anywhere but here, on this frozen lake, miles from his house, with a damned bear and his crying brother and the long day ahead of him in the cold with his father. He was ashamed that he hadn’t been able to think of something better to write on his paper boat—he should have wished for his family to be together again, for his father to be sweet like he was before Dmitri was born. Instead he’d been so nervous to finish his boat before his father got impatient that he scribbled I want a dog even though there was no point in wishing for something like that. He would either get a dog or he wouldn’t, and luck had nothing to do with it.

“What did you wish for, Dmitri?” he asked but his brother didn’t answer. He didn’t have to. Jesse knew that Dmitri wanted only for his father to come home. Dmitri, the favourite. Dmitri, the good. Dmitri, with the wavy hair of his mother. Dmitri, with the innocent face full of freckles.

The boys walked along the ice until they saw the blue paper boats ahead of them, sodden, half-submerged in an inch of snow. One had begun to unravel and lay on its side. The thaw would not carry them to the reservoir. They would be buried in the snow, destroyed, forgotten. Jesse felt a horrible ache in his chest.

Dmitri stood shivering, his head down and tears in his eyes, while Jesse knelt and unfolded the sturdiest-looking boat, removed the penny and set it on the ice. His father wrote in uneven capital letters, much of it already wet and illegible. It was surprisingly long—almost a full page. He must have written it before he picked them up.

I WANT TO HAVE A REAL, SINCERE TALK WITH EVELINA AND TELL HER I’M GETTING REMARRIED.

The ice shifted underneath his feet, and Jesse snapped his head up, grabbed Dmitri so he wouldn’t fall. Their father should not have left them out here, not even for five minutes. “Don’t make me angry,” Jesse muttered. It was something his father said and he found himself saying the same words—Don’t make me angry, you don’t want to make me angry. He felt the burn of rage spreading through his chest and into his throat and behind his eyes. It was time, Jesse thought, to teach his father a lesson.

By a frozen lake, ten-year-old Jesse waits for his father.

It's New Year's Day, and his dad promised a fresh start.

But Jesse messed it all up.

And that's when he meets the woman.

In the months ahead, the woman's sudden disappearance sets off a chain of events in Whale Bay, spanning out like fracture lines into the lives of her husband, the detective trying to solve her case, and of Jesse and his family - a young boy cracking like ice under the weight of a terrible secret. How A Woman Becomes a Lake is a chilling literary mystery that asks what happens when we are failed by the ones we love.