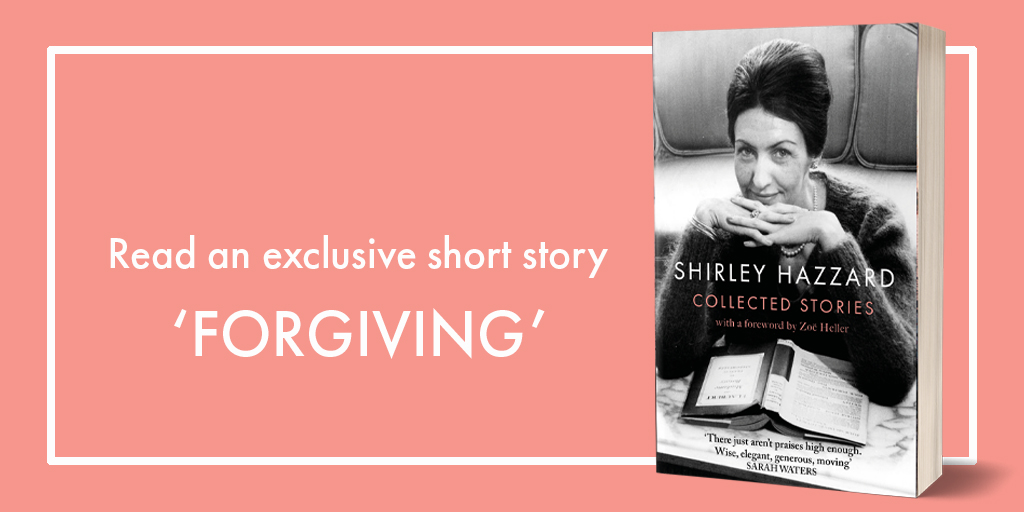

Read an exclusive extract from Shirley Hazzard’s Collected Stories

“Lucas,” she said, crossing the lawn and sitting down on the grass beside him, “they will never forgive us for this.”

He was smoking a cigarette, the other hand gripping his wrist around his bent knees. “What we have to say to each other,” he said, “is more important than going to a dinner party.” He spoiled the resounding effect of this by asking, “What did you tell them?”

“I said that you were sick and I had to stay with you.” She sat sideways, and the folds of her skirt almost covered her bare feet. “I don’t think they believed me—I’m not much of a liar.” She thought she saw his eyes widen, and flushed. She tore up a few blades of grass and rolled them between her fingertips. “The grass is quite damp,” she said. “Perhaps we should go inside?”

“No,” he said. “It’s pleasant here.”

The house, although built inside a wood, was on a gradual slope, so that their view was framed but not obscured by trees. Below the wood, cultivated land—scarcely any of which was theirs—stretched across a little valley and up the opposite hill. The few lights already glowing in the warm evening came from farms or from other summer houses, or belonged to cars that passed along the road at the end of the valley. Their own house, eh, at their backs, was unlit, sharply white in the fading sunshine — a small Greek-revival house just large enough for two people. For years Lucas

had talked of adding a wing so that their occasional summer guests might be more comfortable, but in fact the house could only be extended at the sacrifice of its proportions. The wing had stayed unbuilt and the guests continued to sleep in the living room, able to return to town as soon as possible. Kate and Lucas had no children.

“Yes, it is lovely this evening,” she agreed, enlarging his more moderate remark. She waited for him to speak again, but he only threw the end of his cigarette into the grass.

“Should you do that?” she asked. “Is it safe?”

“You just said the grass was damp,” he pointed out.

She thought, dejectedly, that a sudden conflagration would at least divert him from what he was about to say, but the moments passed with no delivering outbreak of flames, the cigarette having disobligingly fizzled out in a patch of clover. She wished she had brought a sweater for her bare shoulders, but did not like to go inside for one now. She changed her attitude and sat, like him, hugging her knees. “Let’s hope they won’t drive over to see how you are, and find us sitting out here.”

Again he did not reply, and she was left to feel that her remarks were received as crude attempts at appeasement—which they were. She looked at him, and he lighted another cigarette, throwing the match away with a certain insistence. Then he said, “I just can’t get used to it.”

She said, cautiously, “I’m not quite sure what you feel.”

“Well, I feel—all the classic symptoms, I suppose.” He made a brief ironical movement with his shoulders. “Like the deceived husband in a play. I keep telling myself that after all it doesn’t matter, you didn’t mean it, it’s only what I’ve done myself, but I still can’t get used to it.”

She curled her toes in apprehension. “From what you said this morning, I take it you don’t intend to do anything about it?”

“Do anything? What should I do?”

“I mean,” she said, knowing he had understood her, “that you don’t intend to leave me.”

“It doesn’t seem on that scale, does it? From what you tell me. What was it you said it was—an aberration?”

“An incident.” Without turning to her, he suddenly burst out, “Ah, Kate, how could you?”

Twisting her fingers together around her knees, she said in a small, gruff voice, “You leave me alone too much.”

“It’s not my idea, for God’s sake. What can I do, if they send me on these trips? It’s the way I earn my living, after all.” (“And yours” fitted neatly into a small pause.) “I don’t choose it.”

“You might be less enthusiastic about it. I mean, you could—object more.”

“There wasn’t anyone else who could do this last trip.”

“You were away for two months,” she said.

“Well, one doesn’t go to Africa for the day, you know.” He stopped, surprised to find himself in a defensive position. She said, seeing this, “I’m not justifying myself.”

“Hardly,” he replied, ungenerously.

“Lucas,” she said, not daring to touch him, but laying her hand on the grass between them, “you are right to mind. I would hate it if you didn’t, and I’m terribly, terribly sorry. But it was just silly, that’s all. It didn’t matter. Please don’t think it mattered.”

“That seems, somehow, to make it worse.” He drew on his cigarette.

“Yes, I do mind. Of course I mind. I mind like hell.”

“Don’t,” she said.

“What did you expect?”

“In the first place, I didn’t think you’d—know,” she said, barely hesitating to make the correction. “And then, I suppose I thought you would be more—philosophical about it.”

“I can only say that you have a curious idea either of philosophy or of me.”

She laid the side of her head against her knees. “Lucas—don’t be so cold with me,” she said. “Please don’t be.” The darkness was coming down quickly and she could hardly see him now: he was a black, self-contained shape, a ship exuding smoke and showing a single light. “We talk like a couple of stage Englishmen. I would really rather that you hit me.”

“Don’t be melodramatic—you know you’d have a fit if I hit you.” He eh, did agree, nevertheless, that his idea of acceptable behavior had left him no way of dealing with such a discovery.

A mosquito was biting her ankle; she felt that at this juncture she had no choice but to disregard it. He went on. “It must make a difference.”

“Everything makes a difference.”

Annoyed by the solecism, he said, “Do you think I can ever be away from you again without thinking of this?”

She said, without spirit, “The other possibility would be not to go.”

“You’re unreasonable,” he replied in a hard voice.

“In any case, it’s not as though it had ever happened before. Or would again.”

“I have no way of knowing that.”

“Except that I tell you.”

“Then why has it happened now? Kate, can you tell me why?”

The cars could be heard swishing along the main road. She put her cheek back on her knee and stroked her palms over the grass on either side of her. She said, apparently with total irrelevance, “It was my birthday.”

“What?”

“I hadn’t heard from you for weeks. And it was my birthday.” She sighed.

“That’s all. I know it doesn’t help.”

“A form of celebration, I take it?”

She turned her face away.

After a moment he said, “The photograph you sent me, then—he took that?”

“What photograph?”

“A photograph taken up here. On your birthday, you said.”

“Oh. Oh, yes. . . . I’m sorry. Yes.”

“Kate,” he said, aghast, “don’t you have any sensibilities at all?”

“Well,” she said helplessly, “you kept asking for a photograph.”

“I hardy imagined you would go to such lengths to obtain one. . . . How could you send that to me?”

She made an ineffectual gesture toward him. “It was the only one I’ve ever liked.” Her voice, inexcusably, carried the suggestion of a smile.

“It didn’t look a bit like you,” he said crossly. They sat for a while without speaking. Presently he said, with an air of monumental acceptance,

“Perhaps this is the customary thing. Perhaps one has no right to ask loyalty.”

“Perhaps one has no right to expect it,” she said. “But I think one must ask it.”

He was silent again, making it clear that she had forfeited her right to adjudicate human behavior. He could tell, from the interruptions of her breathing, that she had begun to cry. He said unyieldingly, “Now Kate, pull yourself together,” and added, as though tears were by nature frivolous, “this is serious.”

“Yes, I’m sorry,” she said, not raising her hands from the grass but rubbing her tears off on her skirt with motions of her head. “It’s only because I’m tired. I couldn’t sleep last night. In fact, I felt quite shaky all day.”

He doubted this, but dared not say so. Once, years ago, he had expressed skepticism about an illness of hers, and she had promptly and irrefutably fainted, in a shop; since then she had been, in this respect, unchallengeable. Now, however, having dried her eyes, she began to cry all over again and with such a suppressed, pathetic sound that he could no longer ignore it. He said, in a milder tone, “Kate, please stop.”

“I’m sorry,” she said again, “but it’s the way you speak to me.”

“But, dear,” he protested, with a sense of injustice, “I can’t pretend this is nothing. I’m only trying to make you understand how much it matters to me.”

She looked up at him in the darkness. “I can’t help feeling,” she said, and again he could hear her smile, “that you might have accomplished your object with a quarter of the exertion.” She gave a sharp sniff. “I don’t have a handkerchief.”

“Nor do I. We’ll go in, in a minute.” He put his cigarette out carefully in the damp earth.

“Lucas,” she began, “if it would help—I can tell you how it happened.”

“Please don’t,” he said, his voice rising again. “I couldn’t bear to know any details.”

She was silent, and then said, “How strange—it’s so what a woman would want to know. Isn’t that interesting?”

“No,” he said, but almost laughed. They were quiet for a while, and eh, when he next turned his head he said, “Kate,” sharply, as if she might have disappeared in the meantime. “Let us go in.” He got up quickly and, feeling for her hand in the dark, helped her to her feet. He could not embrace her so soon without diminishing the significance of all he had said, and he let her go abruptly—thinking (mistakenly) that she would not have detected the passing of his anger.

They stood for so long, however, facing each other, unseeing, that he was obliged either to speak or to take her in his arms, so he said into the darkness, “About the letters—I probably should write more.”

She touched his hand lightly. “Don’t.”

“No, really, I think you have a point.”

“Lucas,” she said, “I’ll cry again.” He put his arm about her shoulders and they crossed the lawn awkwardly, holding each other and out of step.

“Be careful,” she said. “I left the watering can somewhere round here.”

“What a dark night,” he said, as they went up the path to the house. They stopped and stared at the sky. “Perhaps it’ll rain. I’m glad we didn’t go out to dinner.”

They walked on. They had almost reached the door of the house when she stood still again, within his arm, and said, “Lucas—what did you mean when you said that it was only something that you’d done yourself?”