Marilynne Robinson, a Reader’s Guide.

‘I have found that when you write a novel, a character never actually leaves you from that point on.’

MARILYNNE ROBINSON

Regarded as one of America’s most important, graceful and original writers, Marilynne Robinson is loved for her deep humanity and prized for her generous intellectual rigour. In many ways an uncategorisable writer, she will be forever cherished as the creator of some of the most memorable fictional characters, including Jack Boughton, John Ames and Lila Ames from her Gilead quartet, and Lucille and Ruth from Housekeeping.

Marilynne Robinson has spoken of her enduring relationship with them: ‘I have found that when you write a novel, a character never actually leaves you from that point on.’

Born Marilynne Summers in 1943 in Sandpoint, Idaho, the town she used for the backdrop of her first novel, Housekeeping, she is the youngest of two. Her father worked in the timber industry and her mother kept home for the family. When Marilynne was young, her brother declared that he would be an artist and she would be a poet. David Summers became a Renaissance art scholar and painter, and Marilynne dedicated her collection of essays When I Was a Child I Read Books to him, ‘the first and best of my teachers’. She was brought up Presbyterian but became a Congregationalist, strongly influenced by John Calvin.

She graduated from Brown University, where she studied American Literature, and while she was at the University of Washington, studying for a PhD in English (on Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 2), her first novel about two little lost sisters began to take shape. She married and had two sons, though later divorced, and wrote Housekeeping in the evenings after the children went to bed. Motherhood influenced that first novel: ‘It changes your sense of life, your sense of yourself.’ She showed her manuscript to a friend who, unbeknownst to her, sent it to Ellen Levine, a New York literary agent. The agent loved it but took it on with the caveat that she thought it would be hard to find a publisher. She did find one in Farrar Straus and Giroux (and Faber in the UK), who said they loved it but that it would be hard to sell. Housekeeping was published in 1980 and an early review by Anatole Broyard in the New York Times turned out to be only the first to laud this masterpiece:

‘You can feel in the book a gathering voluptuous release of confidence, a delighted surprise at the unexpected capacities of language, a close, careful fondness for people that we thought only saints felt.’

The novel went on to win the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction and was shortlisted for the Pulitzer Prize.

It looked like an exciting new career had been launched. But Marilynne Robinson had other things to occupy her.

Instead of writing another novel, she turned to years of deep study of political and theological subjects and began to write non-fiction. Her first, written during a brief spell living in England, was Mother Country: Britain, the Welfare State, and Nuclear Pollution (1989), an indictment of the nuclear power industry. Then followed The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought (1998) on, among others, Darwin, Calvin and Nietzsche.

In 1991 she was invited to teach at the famous Iowa Writers’ Workshop at the University of Iowa; founded in the 1930s, this was America’s first creative writing degree programme. She remained there for twenty-five years, dividing her time between Iowa and a home in Saratoga Springs in upstate New York.

Essay-writing, teaching, reading, reviewing and studying she did plenty of, but she eschewed fiction. Until, two decades after the publication of Housekeeping Marilynne Robinson was spending several days in a largely empty hotel in Provincetown, Massachusetts, waiting for her grown sons to join her for Christmas, and found herself ‘in a little room with Emily Dickinson light pouring in through the windows and the ocean roaring beyond. I had a spiral notebook, and I started thinking about this situation and the voice. And I started writing.’

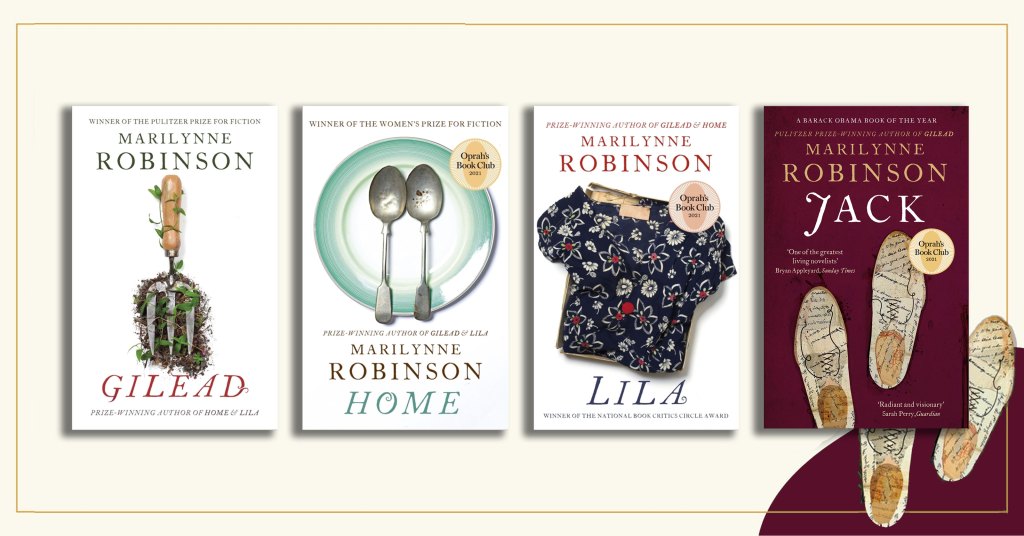

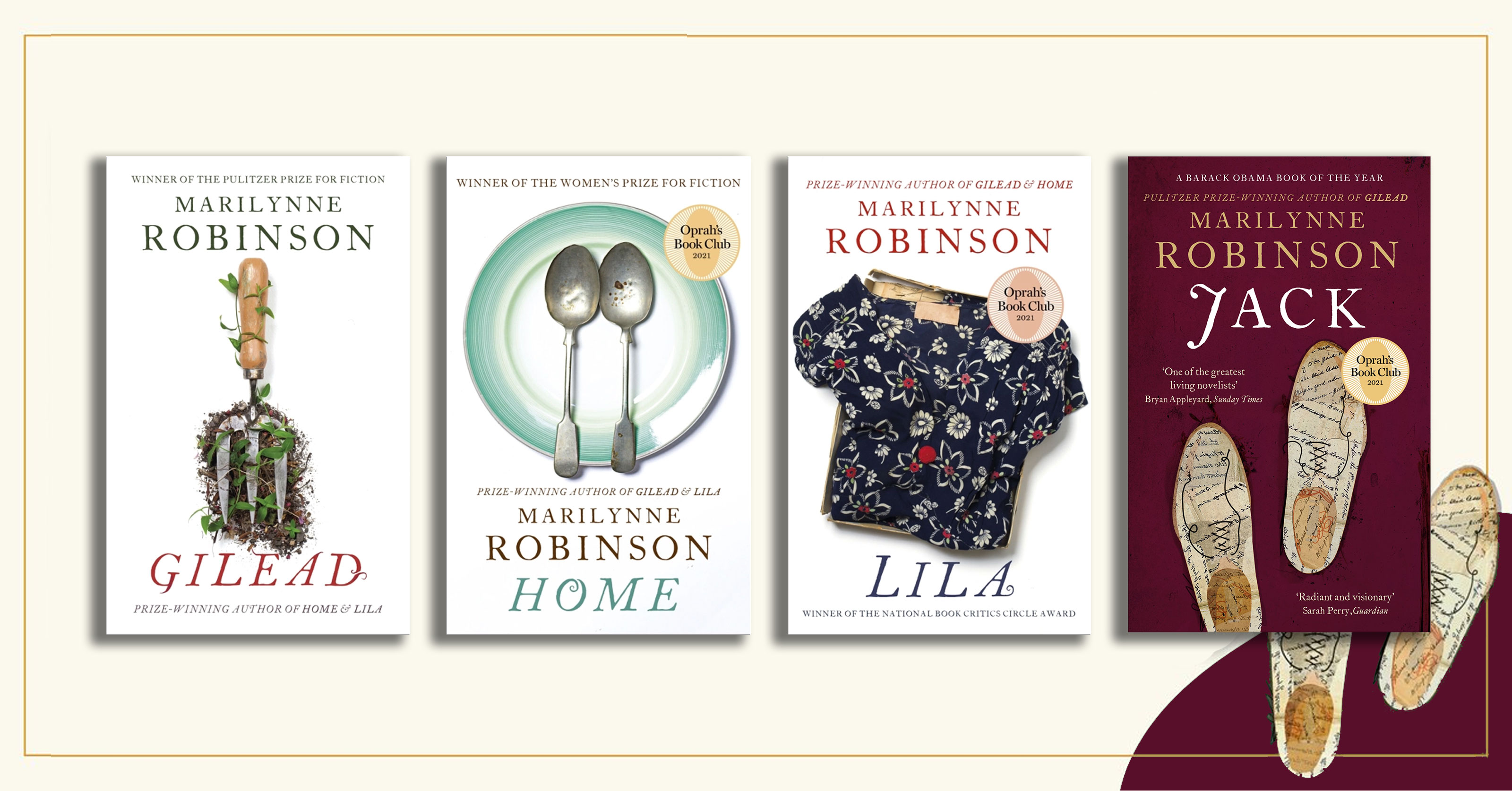

Gilead was the extraordinary result. Published in 2004, it was widely praised throughout North America, Britain, Australia and Europe and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction It was translated into over thirty languages. Agents, publishers and readers wondered, what next?

The answer, to everyone’s surprise, came just four years later, when Marilynne returned to the fictional town of Gilead in Iowa in Home (2008).

‘After I write a novel or a story, I miss the characters – I feel sort of bereaved. So I was braced for the experience after Gilead. Then I thought, If these characters are so strongly in my mind, why not write them? With Jack and old Boughton especially, and with Glory also, I felt like there were whole characters that had not been fully realized in Ames’s story. I couldn’t really see the point in abandoning them.’

Home won the 2009 Orange Prize for Fiction (now the Women’s Prize).

Marilynne continued to write essays and lectures, which were collected in Absence of Mind: The Dispelling of Inwardness from the Modern Myth of the Self (2010) and When I Was a Child I Read Books (2012).

But it seemed that the town of Gilead had not released its creator just yet, and in 2014 she told the poignant and fascinating story of John Ames’s wife in Lila.

Essay collections The Givenness of Things (2015) and What Are We Doing Here? (2018) followed.

The Gilead trilogy, as it was then, has been forever haunted by dear Jack. Boughton’s precious son, Glory’s brother and John Ames’s namesake, Jack has raised hopes, created disappointment and left sadness in his wake throughout his life. He is the wayward son of Gilead, a ne’er do well, a man to test the patience and humanity of all he encounters. But he is also deeply loved.

And now we are rewarded with Jack’s novel. Set in the 1940s, just a few years before Gilead, it is a moving love story between Della, a black woman, and Jack, at a time when interracial relationships were illegal in more than half of the United States.

Though not in Iowa. Legally, Jack could bring Della home to Gilead. However . . .

Jack, the book that makes this extraordinary series a quartet, is about love and forgiveness. Marilynne Robinson has given us a beautiful and poignant novel that asks us to understand the true definition of grace.

THE NOVELS

The main characters of the Gilead quartet:

John Ames,

preacher, married to Lila Ames

Robert Boughton,

preacher, widower

Jack Boughton,

son, jack-of-all-trades,

married to Della Miles

Glory Boughton,

ex-teacher, daughter

Della Miles,

teacher, married to Jack Boughton

Marilynne Robinson’s novels have a particular flavour. They are all set in a small town, all strongly driven by singular characters; they explore with a wonderfully gentle and wise humour what ordinary lives feel and look like. On one level they are circumscribed stories: limited landscapes, few characters, no driving plot, small concerns . . . And yet, and yet . . . In the particular is the world, and what these novels are about is no less than the universal concerns of almost everyone on this earth. ‘Ordinary things have always seemed numinous to me,’ she says, and amply demonstrates that in her fiction.

Character is her lodestar: ‘I feel strongly that action is generated out of character. And I don’t give anything higher priority than character.’ From the intricacies of character she spins her novels.

‘But then literature is full of whale hunts and sword fights and wars in heaven. My fascinations are what they are. I love loyalty and trust, and courtesy, and kindness, and sensitivity. They are beautiful things in my mind. They require alertness and self-discipline and patience. And they are qualities that sustain my interest in my characters.’

But she also talks about how human experience ‘does not resolve into being comfortable in the world . . . including doubt and sorrow. We experience pain and difficulty as failure instead of saying, I will pass through this . . . We should think of our humanity as a privilege.’

These qualities, these everyday problems and gratifications are, in the strong, lyrical, metaphorical prose that Marilynne has made her own, what makes her work so powerful and touching. At the core of her writing is absolute respect for people. She has often talked of the awe in any human interaction and the richness of our lives through such encounters, and our attempts to understand one another through observing ‘a music of words and hesitations’.

As with most novelists, she is a little mysterious about where she draws her inspiration from, but she mentions often how a voice is where she starts and that after years of reading theology, without any idea of writing another novel, John Ames of Gilead arrived in her head. He was a fully formed man with a particular cadence and attitude; gentle, a little puzzled by the life he’d been given and was soon to leave. He was a man with complexity that she wanted to get to know better. And the same thing happened with Housekeeping. She says she never forms a plan, the voices and the stories ‘just come to me’:

‘[My writing] is just voice-governed. When I think of a character like Lila, then I have to think of the kind of language that would be available to her. And the same with John Ames: he has his own little world of dialogue – or large world, I should say. I don’t have much sense of myself as a writer apart from what I write. It’s the voice that’s in my mind that governs what I write.’

Marilynne does very little in the way of revising. Instead of going over and over a scene or passage until she gets it right, when something is not going well, she stops. She walks, thinks, muses and only when the voice has returned with clarity, no matter how long it takes, only then, does she continue. The revision is in the mind, not worked out on the page.

Questions for Readers and Reading Groups

1. Can we know each other? ‘I don’t think in an essential way that ever happens. I think books are so fascinating in a way, because they bring you one step closer.’ Do you agree with Marilynne Robinson? Do we know people in books better those we live with?

2. How does Marilynne Robinson create a specific world in Gilead –a small American town with small-town people – that speaks to people everywhere?

3. Jack’s struggle with predestination is fascinating and tragic. He’s given up the church, so why do you think he seeks answers from preachers?

4. Do you think of Jack as a prodigal son?

5. What do you think Marilynne Robinson is telling us about marriage in her novels?

6. Marilynne Robinson gives her characters safe places, but how does she make the reader highly aware of the racism in St Louis as a permanent and frightening backdrop?

7. Marilynne Robinson’s intent in her novels is serious but she also has a generous, gentle humour. Where does the humour reside?

8. Lila and Jack are outsiders and seem to find a mutual understanding as a result. What does that say about the town of Gilead?

9. Marilynne Robinson has said that it intrigued her to try to write the story of a good man in Gilead. Is it harder to write about goodness?

10. Is there a character you would love Marilynne Robinson to write more about?

For more on the Gilead quartet download the full Reader’s Guide here: