An Extract from Lullaby Beach

No more days, no more times, no more tides. No more secrets.

A compelling novel about family secrets and the legacy of trauma, set against the changing fortunes of an English seaside town, from award-winning writer Stella Duffy.

When Lucy discovers the body of her great aunt Kitty, with a puzzling note and empty pill bottles by her bed, she can’t believe that the formidable woman who held her family together is gone – or understand why she has taken her own life.

Lucy is determined to decipher Kitty’s final message. What she finds will overturn everything she thought she knew about her family.

Lullaby Beach takes the reader on a journey through three generations of a complicated, close-knit family whose joys and misfortunes track many of the most pressing conflicts and concerns of post-war Britain, from the promise and hypocrisies of 1950s London to the political divides and risky freedoms of the present day.

Told with the warmth, generosity and fierce passion which has won Stella Duffy so much praise over her career, Lullaby Beach is a brilliant story of loss and love, revenge and redemption.

- * * * * *

London, 1956

The build-up to Christmas meant that more potential investors were in town, more reasons for Danny to show off the gorgeous girl on his arm and for Kitty to be the beautiful attraction, the tempting bauble he dangled before them. Many more reasons for Danny to be seething by the time they reached the south side of the Thames. That night, a fortnight before Christmas, he grabbed her just as they got back into the house at the railway end of Corngate Street. He shoved the door closed, and before Kitty could whisper to him to be quiet, they didn’t want to wake Mrs Kavanagh, he reached for her arm and yanked it high above her head, pushing her back against the hall wall.

‘Danny, what—’ but his mouth was against hers, shut- ting her up.

He kissed her with such force that she couldn’t kiss back; there was nothing to do but receive the pushing of his face into hers, their teeth clashing, his tongue probing her mouth. One arm above her head, the other pinned between her body and his, Kitty’s shoulders were pushed into the tired plaster of the wall, her hips jammed against the dirty old wainscot, the thin wooden ledge where the wainscot met the tired wallpaper jabbing into her back.

He pulled away just enough to rest his heavy head against hers, then he whispered with his mouth right against her ear, his breath full of the night’s wine and brandy, ‘You’re too bloody good at this game, girl. Too bloody good at it by half.’

‘But I don’t know—’

Again she tried to ask what he meant, again he shut her up. This time he clamped his free hand over her mouth, and now she tasted the sweat from fingers that had formed a clenched fist as he barrelled home, smelled tobacco from his roll-ups and the faint scent of the hair oil he’d used before they went out. He shook his head and groaned and she held her breath. She stood, pushed hard against the wall in the hall, and understood that she was here and now and she was also thinking ahead to somewhere else, to a time and place where this wasn’t happening. She was in this night and she was on Christmas Day. Her parents’ guest house was always overheated at Christmas time; they prided themselves on their few winter guests never having to complain about the heating, never having to ask for an extra blanket, another hot-water bottle. Kitty might travel down to Westmere in a polo neck, but within ten minutes of her getting in the door her mother would be asking why she was all covered up. In a quiet, careful part of her mind, Kitty took note. From here she could watch herself and make sensible choices, like tempting Danny’s hand away from her throat. She knew that blouses might hide marks on her arms, but she was not a button-to-

the-collar girl, never had been.

Danny was whispering urgently in her ear, ‘God help me, I get so jealous, Kit. I want you all for myself. I know I’m an idiot, I just can’t help it. I get in such a rage and it’s so damn hard to hold it in all night.’

‘But Danny, you want them to look at me like that. That’s the plan, isn’t it?’ She was almost laughing now, her fear washed away by his need, back inside herself.

He shook his head. ‘Yes, only I don’t like it, I don’t like it a blind bit.’

‘Flippin’ heck, I’m the one who doesn’t like it. I do it for you, love, for your work.’

‘Promise?’ he whispered. ‘Promise me faithfully? I need you to be my girl.’

Kitty melted then, melted into him, the last of her fear draining away, and all she felt was his upset and her ability to soothe it. Pinned to the wall by Danny’s longing, she soaked in his need. It was something, the power to be the one he needed, the one he wanted, the one he was scared to lose. She had something.

‘You make me mad, Kitty, you really do.’

Kitty edging them upstairs and Danny’s hand on her cheek, almost a tap, almost a slap.

‘You drive me crazy, Kit, my lovely girl.’ Fingers twisting into a pinch on her upper arm. ‘God, but I can’t get enough of you.’

The pinch now a punch, light, almost playful. ‘All mine, Kit, all mine.’

The day before Christmas Eve, Kitty came back from her shift to find a note pushed under her door. It was from Ernestine, asking if she’d like to join her for a drink. She turned the note over in her hand, wondering if she could. Danny was down in Westmere for his family’s big Christmas party – his mother would have his guts for garters if he didn’t turn up – and Kitty was due back at her parents’ guest house early on Christmas Eve afternoon.

Kitty frowned at the note, written in Ernestine’s beautiful copperplate writing. She’d love to go out for a drink, it was Christmas after all, but Danny had turned up unexpectedly before now and he always hated it when she was out, treated it as if she’d disappointed him on purpose and either sulked for half the night or took it out in nastier ways. Kitty had learned it was easier just to stop in. At least she thought it was, but then the last time it had happened he’d been quite different. She’d come in a bit merry from a night at the pictures and a quick port and lemon down the road with Ernestine, and as she put her hand on the door to her room, she had a sudden knowledge that Danny was there, waiting. The light was off and she could see the little red glow of his cigarette from where he sat on the bed on the other side of the room.

‘Danny?’ she asked, worried.

‘You’re all right, darling,’ he answered.

As she was lifting her hand to flick on the light, he spoke quietly from the dark. ‘Come over here, lovely girl.’

She crossed the room, slipping off her shoes as she did. The port and lemon turning in her stomach, her breath held. He’d burned her once before with his cigarette, swore blind it was an accident, though she hadn’t been sure. She wasn’t sure now.

‘I’d have stopped in if—’

He cut her off with a laugh. ‘You’re your own woman, Kit, that’s one of the things I like about you.’

Kitty didn’t know what to make of it. He reached over to put out his cigarette in the heavy glass ashtray on the bedside table and stretched out for her hand in the semi-darkness. Danny pulled her to the bed, laid her down beside him and kissed her slowly and softly for so long it felt like he was wooing her all over again. In her hunger for him, for his lips on her mouth, his hands on her body, Kitty forgot how unpredictable she knew him to be, all she knew was how he made her feel, awake and alive and as if all was right with the world.

Later, after the kissing, after making love, after the gentle slide into each other, curled as one, she whispered, ‘That was different.’

She could feel his slow smile against her forehead, his lips forming a kiss. ‘I’d hate to be predictable, Kit,’ he said, his breath warm and whisky-scented against her hairline. ‘Best keep you on your toes, eh, girl?’

She remembered that night as she stood there holding Ernestine’s note. How pleased he had sounded with himself when he said ‘best keep you on your toes’.

Two hours later, Kitty was on her third whisky mac and Ernestine was slowly working her way through the version of rum punch she’d concocted from the glasses of white rum, dark rum and bitter lemon she’d ordered and the orange she had bought especially at the market in The Cut.

They were drinking at a pub near the Elephant, much further from Corngate Street than the dozen or more around the station, but it was somewhere Ernestine felt more com- fortable, ‘I prefer not to be the only one in a room if I can help it,’ she’d explained to Kitty.

The White Lion, run by two queer blokes, welcomed blacks, Irish, women drinking alone and even dogs, as long as they weren’t what the landlords called ‘soppy little snivelling lapdogs’. Kitty thought the landlords were awfully tough for a pair of poofs, not at all like the queer couple who had a guest house on one of the side streets in Westmere. Her mother had warned Kitty and her brother – Geoff especially – away from that house when they were little, telling them not to talk to the two gen- tlemen who owned the place, and certainly not to engage with any of their guests. Obedient as ever, Geoff thought no more of it and went a different route down to the bus stop, but Kitty took her mother’s prohibition as a challenge and spent a good few months staking out the corner of the street to get a glimpse of the danger lurking behind the dark-blue door with the shiny brass letter box and glorious orange and yellow chrysanthemums in blue-glazed pots that ran up either side of the front steps.

Mostly the only people she saw were men in plain suits like her father’s when he went to visit the bank manager, they parked their nondescript cars and walked up the steps with their heads down and suitcases tightly held. Her waiting was finally repaid when a smartly dressed man pulled up in a green sports car and ran around to open the passenger door, his shoe taps clipping the cobbles of the side street as he did so. He opened the door and out stepped a lady who looked the spit of Lauren Bacall. When they got to the top of the steps, the man rang the bell and the lady turned to look along the lane. The door opened and then, just before she went in, the lady waved at Kitty, who was ten years old and staring in wide-eyed admiration at her golden shoes and golden dress. Kitty held that image of the lovely shiny lady in her mind for months, the kind of lady she wanted to be one day. It was several years later, remembering what she’d seen, that she understood that the gentleman who’d opened the car door with such panache had also been a lady.

Kitty told Ernestine the story of the two ladies and the sparkling shoes and the sports car and they decided they might as well make a night of it; it was Christmas after all and they ordered another round of drinks.

Back in Corngate Street, Ernestine invited Kitty to her room for tea. Kitty loved Ernestine’s room. It was smaller than hers but so much more comfortable. Ernestine was not only earning less than she’d expected, she also sent money home every month to help her family with the younger children, yet somehow her room was warm and inviting. There were cushions made from old clothes bought at a jumble sale and stuffed with older clothes cut into ribbons, and crocheted throws on everything – the bed, the two chairs, and even two hanging on the wall.

Kitty ran her hand along the throw on the bed and asked, ‘Is this what your house in Jamaica looked like?’

Ernestine shook her head as she poured out their tea. ‘My mother’s house is light and bright, windows open on the yard. There are plenty of flowers, she grows her own vegetables and herbs. Here, well, I don’t mean to be one of those people who complains about English weather all the time—’

‘I don’t see why not,’ Kitty laughed, settling in the old arm- chair. ‘English people do. Danny moans about the weather most days.’

Ernestine brought over their tea. ‘I’m sure he does,’ she said lightly.

Kitty looked at her friend. ‘Don’t start.’

‘It’s no good, Kitty. I have something I have to say.’

Kitty pulled the cushion out from behind her back and held it to her chest, a barrier to her heart. ‘Go on then, spit it out.’ ‘I am fond of you, Kitty. We are friends, I think? Good friends?’ Kitty nodded and Ernestine continued, ‘You under- stand that I am a few years older than you, I have had a few

more years around men.’

Kitty started to open her mouth to make a joke about the polite and strait-laced Ernestine having been ‘around men’ but thought better of it as she took in her friend’s expres- sion. ‘Go on.’

Ernestine took a sip of her tea and then she started. ‘It is hard for me, Kitty, to see you wasting your time on a lad like Danny. Hear me out. You’re clever and bright and you have a lovely figure, very pretty face. You come from good people,’ she held up her hand to stop Kitty’s protests, ‘even if yes, your town is terribly boring and there is so much more you could do with your life. I’ve taken it all in. Westmere is no longer on my list of great English seaside destinations.’ She smiled, took a deep breath and went on, ‘You are not me, Kitty, you do not have to make the best of it. You do not have to take a small and damp room in a terrible part of town where everything is dirty and falling down, where you have to cross the street to avoid tramps or drunks or worse—’

‘It’s not that bad,’ Kitty interrupted.

‘It is and you know it is. The only reason you do it at all is for him.’

‘For Danny?’ Kitty answered, irritated, ‘Why not? He’s ambitious, excited about his life, our life.’

Ernestine raised an eyebrow and Kitty wanted to laugh at how teacherly her face was, how serious, but Ernestine was not joking. ‘You may say “our life”, but where is the engagement ring? The proposal? I’m your friend, Kitty, I don’t judge you, but I do have to ask, what’s in this for you?’

‘I’ll tell you what’s in it for me,’ Kitty snapped, hurt and angry. ‘Someone with some gumption. You and your mates off the boat, you’re here, you’re doing something with your lives. I know it’s tough for you, honest I do, but you’re giving it a go. You’re all giving it a go. You know I was telling you that Danny has a party at home? How his mum wanted him to be there?’ Ernestine nodded and Kitty went on, ‘Well, that party happens every year in Westmere and every year my parents don’t get an invitation. They’re not the great and the good. My dad is fine with it,’ she was stumbling over her words as she warmed up to her story, ‘but it’s never been enough for my mum. She’s always said she wasn’t interested in a do like that, but she’d love it, she’d love to be invited, just once.

‘When I was a girl, she wanted to buy the house next door, knock the two into one and make our place a proper hotel, with a lounge bar and everything. There’d have been loads more business, but my dad wouldn’t have a bit of it. My father’s got no ambition and it’s my mother’s life that’s been stifled.’ Kitty shook her head. ‘My dad used to say I was too much like my mum, that’s why we fought like cat and dog. I couldn’t see it when I was at home, but I can see it better now. You’re right, Danny’s not easy. And I don’t have any promises, no ring, no proposal. But maybe that’s the price I have to pay for a lad who dreams big, who wants more than the path marked out for him. At the very least, I’m not going to repeat my mother’s mistakes. My father is a good, kind man, but their life . . . it’s nothing, Ernestine. And that scares me more than anything, giving in to a life like that.’

Ernestine sat quietly, letting Kitty’s words ring around her room. She waited until Kitty was sitting back in her chair, her flushed cheeks a little less red. When she spoke, it was in a quiet but firm voice.

‘There’s no guarantee Danny will give you a better life.’

Kitty smiled, grateful to her friend for her care, no matter what. ‘I know, but he is a way out for me. You did it, you took the only way out you could. You’re battling every flamin’ day when people say bloody awful things and you can’t even get a job you’re properly qualified for—’

‘I know how hard it is for me, Kitty,’ Ernestine said sharply, her quiet words holding back none of the truth.

‘And I want more too,’ Kitty said. ‘I’m not as smart as you, I was breaking my neck to leave school. I have to find my exciting life alongside a bloke who’s prepared to graft for it.’ ‘And when he hurts you? Is it also worth it when he hurts you?’ Ernestine asked, her fingers lightly touching the bruises

on Kitty’s arm, her tone unambiguous.

‘He loves me,’ Kitty said, as if Ernestine had asked a different question.

Discover other titles by Stella Duffy

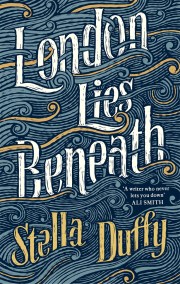

Based on a true story, London Lies Beneath is a compelling historical novel from the award-winning writer Stella Duffy.

'As gloriously alive as the turn of the century south London streets it portrays' RED

In August 1912, three friends set out on an adventure. Two of them come home.

Tom, Jimmy and Itzhak have grown up together in the crowded slums of Walworth. All three boys are expected to follow their father's trades and stay close to home. But Tom has wider dreams. So when he hears of a scouting trip, sailing from Waterloo to Sheppey and the mouth of the Thames - he is determined to go. And Itzhak and Jimmy go with him.

Inspired by real events, this is the story of three friends, and a tragedy that will change them for ever. It is also a song of south London, of working class families with hidden histories, of a bright and complex world long neglected. London Lies Beneath is a powerful and compelling novel, rich with life and full of wisdom.

'Vivid and full of heart, Duffy's new novel is a fitting hymn to the city that inspired it' FINANCIAL TIMES

'A paean not just to South London, but to a vanished way of working-class life . . . Duffy's narrative is as fluid as a costermonger's patter, carrying the reader along' DAILY MAIL

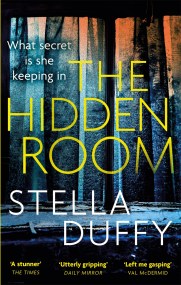

What secrets is she keeping in the hidden room...?

Life is good for Laurie and Martha. They have a beautiful home in the fens, three great kids. Laurie's career as an architect has suddenly taken off.

But when a stranger arrives in town, things begin to go wrong. Martha feels resentful of Laurie's success. Teenage daughter Hope becomes withdrawn and obsessive. And Laurie can do nothing. Because this isn't a stranger. She knows this man all too well - and what he's capable of. He's come back for her. And if she tells anyone the truth - she will lose everything.

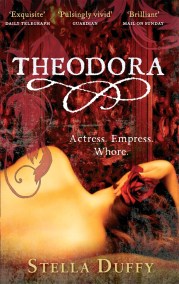

Justinian took a wife: and the manner she was born and bred, and wedded to this man, tore up the Roman Empire by the very roots' Procopius

Charming, charismatic, heroic - Theodora of Constantinople rose from nothing to become the most powerful woman in the history of Byzantine Rome. In Stella Duffy's breathtaking new novel, she comes to life again - a fascinating, controversial and seductive woman. Some called her a saint. Others were not so kind...

When her father is killed, the young Theodora is forced into near slavery to survive. But just as she learns to control her body as a dancer, and for the men who can afford her, so she is determined to shape a very different fate for herself.

From the vibrant streets and erotic stage shows of sixth century Constantinople to the holy desert retreats of Alexandria, Theodora is an extraordinary imaginative achievement from one of our finest writers.