Give Us Freedom, The Story of the Book

Who was the all-time top goal scorer in the 2019 World Cup? Who but the quicksilver forward of the Brazilian women’s football team, Marta Vieira da Silva? When I was a girl, we never played football and never thought we could. ‘Magic Marta’, as they call her, is one of the countless heroines re-writing the old story and opening new worlds for today’s women and girls.

Women playing sports, directing films, becoming leaders in business and politics, are all part of the exciting changes in modern times. The good news is that we don’t all have to be Olympic athletes like Jessica Ennis Hill or Sheryl Sandberg-style brilliant CEOs to share the rewards of the determination and pluck they and others have shown down the years. Even those classed as criminals and outcasts made their mark. One of the female convicts transported to Australia aged fourteen, Mary Reibey, survived to become a super-rich trader and shipowner, and founded the country’s first bank. Three hundred other women prisoners, massed together on a church parade to honour the Governor-General of the Colony, turned their backs on the official party and threw up their skirts to stage a mass mooning, roaring with laughter and beating out a raucous rhythm on their bare backsides.

It’s taken time, of course, and most of these stories were either forgotten or never known. The first British Ladies’ Football Club drew crowds of 60,000 when it was founded in 1895 – who knows that now? Asked who was the first woman to rebel against male supremacy and to declare that women’s inferiority was man-made, not natural, nine out of ten would say Mary Wollstonecraft. They’ve never heard of the fiery champion of women in the French Revolution, Olympe de Gouges, who pitched into the war of words against the male leaders to assert women’s equality, at the cost of her life.

These were some of the peaks of a struggle that dates from the beginning of the modern era, some two hundred years ago. At that time there was no country in the world that men did not control. Men ran everything: the government, the law, finance, religion, the military, while women and the family were their property as well. Each daughter, wife or mother was governed by her male relations, usually forbidden to be educated, to leave home, or even to go outside the house on her own. Working women lived and died in drudgery, often more subject to their menfolk than their more privileged sisters. Even in that group, the rare exceptions who rebelled against the constraints of their class were usually lucky enough to be born clever, rich and ruthless, like the sensational nineteenth-century lesbian Anne Lister, who ruled her Yorkshire estate and beyond under the name of ‘Gentleman Jack’. Even America, a brand-new society founded on the belief that all were born equal, made an exception in the case of women. Man may have been born free, but everywhere woman was in chains, denied the legal and civil recognitions we now call human rights.

As modernisation began and the Industrial Revolution ripped through Britain, women found their traditional home-based lives lost almost overnight as they, their men and their children, were turned into factory-fodder to feed the machines. But the tide of change did not touch the lives of the women and girls in the countries where female hands of all colours but white grew all the tea, coffee and cotton in the world, and picked it and packed it too, but never processed it nor profited from it, and where the most brutal forms of agricultural labour remained their only way of life.

Arguably the women in non-industrialised nations whose traditional crafts could not be mechanised or monetised could be called luckier than their western sisters who were suffering the worst excesses of punitive industrial labour. Millions were not. As the transatlantic slave trade picked up speed into the nineteenth century to supply the labour-hungry New World and its colonies, women in Africa were at first safer than their men, whose size and strength made them more attractive. Alas, countless women in Nigeria, the Congo, Cameroon and Ghana lost their freedom, their ancient way of life and even the right to remain safe in their own homes when the slave-owners figured out that a young woman’s labour could be exploited in two ways. She could work in the fields, and produce up to twenty or more children, all to be sold for ready cash.

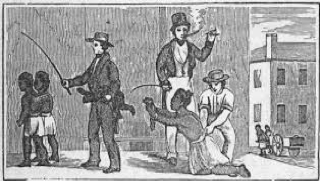

Losing their family, their kin, their country when they were taken – this was only the beginning for the females. The black men had to labour for the white master by day: they did not have to lie with him at night. Nor did they have to suffer, day in, day out, the relentless sexual harassment of the white owners and overseers, which the women had no power to complain about or refuse. One who did was an unknown eighteen-year-old given two hundred lashes for refusing to have sex with an overseer. The revenge of the slighted prick was witnessed by the Dutch-Scots soldier and writer John Gabriel Stedman, who recorded that, stripped to the waist and hanging by her wrists from a tree, she was ‘lacerated in such a shocking manner by the whips of two negro-drivers, that she was from her neck to her ancles (sic) literally dyed with blood’. And who can gauge the mental agony inflicted on the women who had to bear children, knowing that they would be sold and lost to them for ever? Who were compelled to bear many children, but never had a family they could call their own?

How did the slaves themselves react to all this? Here is one of the rebels, Harriet Ann Jacobs, who escaped from her plantation in 1853: ‘God gave me a soul that burned for freedom and a heart nerved with determination to suffer even unto death in pursuit of it!’. Harriet was literate, lucky and extremely brave. Most were not. They could not write and did not dare to speak. One young girl caught the eye of the slave-owning American President Thomas Jefferson and served as his ‘concubine’ for thirty-six years, bearing him seven children, who also became slaves. To resurrect the stories of slave women like this from the graveyard of the past is to give life to millions upon millions of silenced female voices.

Everything changes and nothing stands still, said Heraclitus, introducing his most famous philosophical proposition, the theory of universal flux. Change, argued the old sage, is the fundamental, eternal and prime motor of the universe, the only constant on which we can rely, and it should not be resisted. And the pendulum of history in the modern era was swinging women’s way. A fundamental and world-changing shift in the relationship between the sexes occurred in the mid-1800s, when a handful of rebel women took up the claim to freedom and raised it to a higher plane. The small but powerful Emmeline Pankhurst summed it up: ‘We suffragists have a great mission – the greatest mission the world has ever known. It is to free half the human race, and through that freedom to save the other half’.

A revolution for women?

Yes!

The nineteenth century was to bring not one turn of the wheel but two, as progress for women found its focus on the right to contraception and the right to vote. From the early days of the fight for female freedom, gaining the vote was seen in the West as ‘the Queen of Rights’, the jewel in the crown. Without it, women had no power to choose those who had power over them, the men who made the laws by which they had to live. With it, they could change the laws and the lawmakers too, since the right to vote out an unsatisfactory representative was just as important as the right to vote one in.

But don’t hold your breath.

Not now, girls, not yet . . .

. . . was always the message. In the north of England, the young Emmeline Goulden, later to be Mrs Pankhurst, heard her first suffrage speech as a fourteen-year-old in the 1860s. As the following decades dragged by, hundreds of women put in thousands of hours under the leadership of the mild-mannered Millicent Fawcett, marching, leafletting and lobbying, without result. Fawcett herself said that the movement for women’s suffrage was ‘like a glacier; slow moving but unstoppable’. To Pankhurst, this glacial speed of progress was intolerable. Gallant New Zealand, a small country split between two islands, shamed the so-called ‘Great Powers’ by giving all its women the vote as early as 1893, and Australia followed in 1902. Generous in victory, New Zealand later sent a delegation to England to support the sisterhood there.

New Zealanders had had the vote for a full ten years by the time Pankhurst’s patience ran out. In 1903 she founded the Women’s Social and Political Union with her three daughters Christabel, Sylvia and Adela, determined to give the ‘polite and tame’ movement of the suffragists more urgency and bite. Christabel, always the most belligerent of the women warriors, argued forcefully for creating public protests provocative enough to get the protesters imprisoned, which would infallibly draw attention to the cause. ‘We threw away all our conventional notions of what was “ladylike” and “good form,”’ Mrs Pankhurst remembered, ‘and we applied to our methods the one test question: will it help?’.

It did.

And it changed the world.

For the better, twenty-first century women would say, now we can vote, stand for Parliament and hold public and political offices. For the worse, many thousands thought at the time, when male dominance was the only system that they had ever known. Not only they, but their parents, their grandparents and great-grandparents had grown up with it, and had been taught that it was ordained by God. It was no surprise, then, that the majority of men, and women too, believed that this was ‘the natural order’, and the way things ought to be. The leaders of the long fight for freedom had to face furious opposition from others who could not accept that the age-old suppression of women was wrong.

Chief among them was one who could have done more than any other woman to further the cause of liberty for all her sex, Queen Victoria, the ruler of the greatest empire the world had ever seen. Sadly, the pint-sized potentate, less than five foot tall but one of the most powerful influencers on the planet, did all she could to stop what she called ‘this mad, wicked folly of “Woman’s Rights” with all its attendant horrors’. In her view ‘God created men and women different’ and ‘Woman will become the most hateful, heathen and disgusting of human beings were she allowed to “unsex” herself’.

One of Victoria’s pet hates was the sparky Viscountess Amberley, who toured the country calling for votes for women, equal pay for equal work and equal opportunities for education and employment, just three of the demands in the Articles of Women’s Rights she composed in 1871. A strikingly modern free-thinker, she paved the way for another radical aristocrat, the fearless Lady Florence Dixie. Dixie was the first European woman to enter Patagonia only weeks after the birth of her son and became one of the world’s first war correspondents when she covered the first Boer War for London’s Morning Post. But her ever-fizzing spirit found its main focus in fighting for women, with far-reaching proposals including fully equal legal and property rights, the first born of the British monarch to inherit the throne and freedom for both men and women to wear the clothes currently restricted to the opposite sex.

The suffrage struggle was as long and hard as the resistance it encountered at every stage of the way. It was won by women, for women, whether they wanted it or not. Winning the vote was seen as the supreme victory, the pearl beyond price. But what use was the freedom of the ballot box to a woman who had died in childbirth before she was old enough to vote? Or one whose bladder and bowels had been so mangled by multiple childbirths that she could not leave the house? ‘No woman can call herself free who does not own and control her own body!’ was the rallying cry of Margaret Sanger, the Irish-American campaigner who became known as ‘the Mother of Birth Control’. The battleground was the female body, and only the woman who owned it had the right to determine how she used it, ‘regardless of what the man’s attitude may be’.

Fighting talk for sure, and another long and dirty fight it was, like suffrage. But it was Sanger who tipped the scales when she brought together a research chemist, Gregory Pincus, and a rich feminist, Katharine McCormick, from whose connection the priceless contraceptive pill was born. Cue the summer of love, flower power, women’s liberation and the dazzling high priestess of the sexual revolution, Erica Jong, poet-prophet of the mysterious zipless you-know-what. ‘It is the purest thing there is, rarer than the unicorn, and I have never had one,’ she wrote. For others, once the fight for the vote and for birth control had been won, liberation for women took different forms. Freedom from compulsory wife-and-motherhood was next on the list, and from the suffocating social pressure women suffered from cradle to grave. With them came freedom to work, to travel and to run their own lives, traditionally the birth right of every little boy and almost never of a girl.

Enter battling Betty Friedan, one of the Mothers of the Women’s Movement. Friedan’s great achievement was to explode the ‘Feminine Mystique’ in her ground-breaking work of that name, the myth that every woman’s inborn femininity made her happy as she ‘shopped for groceries, matched slip-cover material, ate peanut butter sandwiches with her children [and] chauffeured Cub Scouts and Brownies’. Friedan herself was an A-student who left college with an armful of awards and a CV that would have guaranteed her a brilliant career, but her then-boyfriend talked her out of it. Housework and motherhood followed until she asked the simple question that kick-started modern feminism, ‘Is this all?’. Working with other bold and brilliant women like Gloria Steinem (‘Steinemite!’), she launched the Women’s Liberation Movement that changed the world again.

Who now remembers the days when girls were not allowed to go to college because they ‘would only get married’, and when they got married they were not allowed to have jobs? This striking and exhilarating change has been the work of the women we celebrate in this book, even as we accept that equality is not yet won. This story has no end, only a new beginning, and we do not know what form that will take. The Founding Mother of Women’s History, Gerda Lerner, put it like this. ‘Men are not the centre of the world,’ she wrote, ‘but men and women are . . . What will history be like when we simply step out together under the free sky?’.

What indeed? Like many children, I cannot remember when I realised that to most people, girls were less important than boys. At university, no one questioned the fact that there were five colleges for women, and twenty-nine for men. As a young woman trying to get a job, I was routinely asked, ‘You’ve got a wonderful husband and two lovely children, what are you compensating for?’.

Events like these are less likely to happen now that women have built a history of rebelling against their long-established role as no more than life-support systems for society, children and men, and have emerged as strong and significant in their own right. It has been a thrilling task to track the stories of these extraordinary women who have worked together to re-make our world. The freedom they have won for women has been in an unofficial alliance with other groups, including good men, when liberating girls from the narrow demands of compulsory wife and motherhood has allowed boys too to choose a different path. The Women’s Movement has grown up and come of age at the same time as the wider LGBT+ community, Black Lives Matter, anti-racist protests, and calls for diversity, all creating a more inclusive and a better society for us all.

Rebel women have spent the last two hundred years thinking the unthinkable, dreaming of change, and making it come true.

A female premier?

A female president?

A female pope?

Why not?

In the twenty-first century we are looking forward to a world that offers many more opportunities to follow in the footsteps of all my rebel women.

They are the lamplighters who have gone before and we must not let them down.

Let us not rest till all of us are free.

Previously published in as Rebel Women.