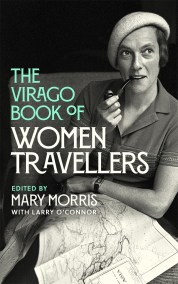

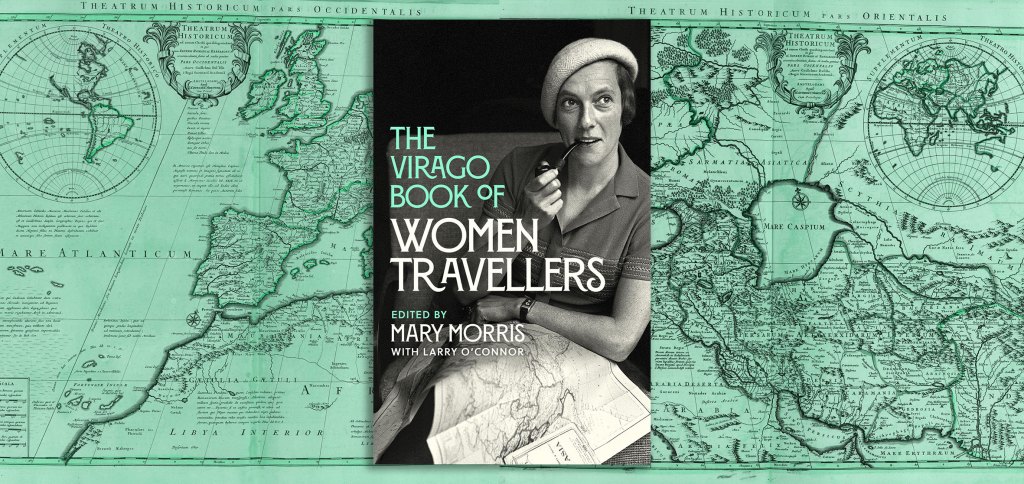

The Virago Book of Women Travellers: Edith Wharton

‘A volume in which rich and unexpected seams of precious materials await discovery’ Guardian

Three hundred years of wanderlust are captured in this collection as women travel for peril or pleasure, whether to gaze into Persian gardens or imbibe the French countryside, to challenge the fierce Sahara or climb an impossible mountain.

Whether it is curiosity about the world, a thirst for adventure or escape from personal tragedy, all of these women are united in that they approached their journeys with wit, intelligence, compassion and empathy for the lives of those they encountered along the way.

***

EDITH WHARTON

(1862–1937)

Until quite recently, Edith Wharton has too often been dismissed as an aristocratic grand dame who divided her time between the glittering high societies of New York and the Continent, and an author whose work didn’t measure up to that of her friend and literary companion, Henry James. Quite to the contrary, though, her fiction – The House of Mirth, the Pulitzer Prize-winning The Age of Innocence, and the acclaimed novella Ethan Frome – are masterworks of psychological insight and social nuance. But Wharton also had an exacting eye as a traveler and wrote some of her most luminous descriptive prose while abroad. A prose classic – almost an extended poem – In Morocco is a haunting mix: the exotic, infinite beauty of Marrakech and the restrained prose of Wharton. Her selection of detail (‘sunlight through the thatch flames on round flanks of beaten copper’) catches the spirit of the place.

***

- From

IN MOROCCO

The Bahia

Whoever would understand Marrakech must begin by mounting at sunset to the roof of the Bahia.

Outspread below lies the oasis-city of the south, flat and vast as the great nomad camp it really is, its low roof extending on all sides to a belt of blue palms ringed with desert. Only two or three minarets and a few noblemen’s houses among gardens break the general flatness; but they are hardly noticeable, so irresistibly is the eye drawn toward two dominant objects – the white wall of the Adas and the red tower of the Koutoubya.

Foursquare, untapering, the great tower lifts its flanks of ruddy stone. Its large spaces of unornamented wall, its triple tier of clustered openings, lightening as they rise from the severe rectangular lights of the first stage to the graceful arcade below the parapet, have the stern harmony of the noblest architecture. The Koutoubya would be magnificent anywhere; in this flat desert it is grand enough to face the Adas.

The Almohad conquerers who built the Koutoubya and embellished Marrakech dreamed a dream of beauty that extended from the Guadalquivir to the Sahara; and at its two extremes they placed their watch-towers. The Giralda watched over civilized enemies in a land of ancient Roman culture; the Koutoubya stood at the edge of the world, facing the hordes of the desert.

The Almoravid princes who founded Marrakech came from the black desert of Senegal; themselves were leaders of wild hordes. In the history of North Africa the same cycle has perpetually repeated itself. Generation after generation of chiefs have flowed in from the

desert or the mountains, overthrown their predecessors, massacred, plundered, grown rich, built sudden places, encouraged their great servants to do the same; then fallen on them, and taken their wealth and their palaces. Usually some religious fury, some ascetic wrath against the self-indulgence of the cities, has been the motive of these attacks; but invariably the same results followed, as they followed when the Germanic barbarians descended on Italy. The conquerors, infected with luxury and mad with power, built vaster palaces, planned grander cities; but Sultans and Viziers camped in their golden houses as if on the march, and the mud huts of the tribesmen within their walls were but one degree removed from the mud-walled tents of the bled.

This was more especially the case with Marrakech, a city of Berbers and blacks, and the last outpost against the fierce black world beyond the Atlas from which its founders came. When one looks at its site, and considers its history, one can only marvel at the height of civilization it attained.

The Bahia itself, now the palace of the Resident-General, though built less than a hundred years ago, is typical of the architectural megalomania of the great southern chiefs. It was built by Ba-Ahmed, the all-powerful black Vizier of the Sultan Moulay- el-Hassan (reigned from 1873–1894). Ba-Ahmed was evidently an artist and an archaeologist. His ambition was to re-create a Palace of Beauty such as the Moors had built in the prime of Arab art, and he brought to Marrakech skilled artificers of Fez, the last surviving masters of the mystery of chiselled plaster and ceramic mosaics and honeycombing of gilded cedar. They came, they built the Bahia, and it remains the loveliest and most fantastic of Moroccan palaces.

Court within court, garden beyond garden, reception halls, private apartments, slaves’ quarters, sunny prophets’ chambers on the roofs and baths in vaulted crypts, the labyrinth of passages and rooms stretches away over several acres of ground. A long

court enclosed in pale-green trellis-work, where pigeons plume themselves about a great tank and the dripping tiles glitter with refracted sunlight, leads to the fresh gloom of a cypress garden, or under jasmine tunnels bordered with running water; and these again open on arcaded apartments faced with tiles and stucco- work, where, in languid twilight, the hours drift by to the ceaseless music of the fountains.

The beauty of Moroccan palaces is made up of details of ornament and refinements of sensuous delight too numerous to record; but to get an idea of their general character it is worthwhile to cross the Court of Cypresses at the Bahia and follow a series of low-studded passages that turn on themselves till they reach the center of the labyrinth. Here, passing by a low padlocked door leading to a crypt, and known as the ‘Door of the Vizier’s Treasure-House,’ one comes on a painted portal that opens into a still more secret sanctuary: the apartment of the Grand Vizier’s Favorite.

This lovely prison, from which all sight and sound of the outer world are excluded, is built about an atrium paved with disks of turquoise and black and white. Water trickles from a central vasca of alabaster into a hexagonal mosaic channel in the pavement. The walls, which are at least 25 feet high, are roofed with painted beams resting on panels of traceried stucco in which is set a clerestory of jewelled glass. On each side of the atrium are long recessed rooms closed by vermilion doors painted with gold arabesques and vases of spring flowers; and into these shadowy inner rooms, spread with rugs and divans and soft pillows, no light comes except when their doors are opened into the atrium. In this fabulous place it was my good luck to be lodged while I was in Marrakech.

In a climate where, after the winter snow has melted from the Adas, every breath of air for long months is a flame of fire, these enclosed rooms in the middle of the palaces are the only places of refuge from the heat. Even in October the temperature of the Favorite’s apartment was deliciously reviving after a morning in the bazaars or the dusty streets, and I never came back to its wet tiles and perpetual twilight without the sense of plunging into a deep sea-pool.

From far off, through circuitous corridors, came the scent of citron-blossom and jasmine, with sometimes a bird’s song before dawn, sometimes a flute’s wail at sunset, and always the call of the muezzin in the night; but no sunlight reached the apartment except in remote rays through the clerestory, and no air except through one or two broken panes.

Sometimes, lying on my divan, and looking out through the vermilion doors, I used to surprise a pair of swallows dropped down from their nest in the cedar-beams to preen themselves on the fountain’s edge or in the channels of the pavement; for the roof was full of birds who came and went through the broken panes of the clerestory. Usually they were my only visitors; but one morning just at daylight I was waked by a soft tramp of bare feet, and saw, silhouetted against the cream-colored walls a procession of eight tall negroes in linen tunics, who filed noiselessly across the atrium like a moving frieze of bronze. In that fantastic setting, and the hush of that twilight hour, the vision was so like the picture of a ‘Seraglio Tragedy,’ some fragment of a Delacroix or Decamps floating up into the drowsy brain, that I almost fancied I had seen ghosts of Ba-Ahmed’s executioners revisiting with dagger and bowstring the scene of an unavenged crime.

A cock crew, and they vanished . . . and when I made the mistake of asking what they had been doing in my room at that hour I was told (as though it were the most natural thing in the world) that they were the municipal lamp-lighters of Marrakech, whose duty it is to refill every morning the two hundred acetylene lamps lighting the Palace of the Resident-General. Such unforeseen aspects, in this mysterious city, do the most ordinary domestic functions wear.

-

The Bazaars

Marrakech is the great market of the south; and the south means not only the Atlas with its feudal chiefs and their wild clansmen, but all that lies beyond of heat and savagery: the Sahara of the veiled Touaregs, Dakka, Timbuctoo, Senegal and the Soudan. Here come the camel caravans from Demnat and Tameslout, from the Moulouya and the Souss, and those from the Atlantic ports and the confines of Algeria. The population of this old city of the southern march has always been even more mixed than that of the northerly Moroccan towns. It is made up of the descendants of all the people conquered by a long line of Sultans who brought their trains of captives across the sea from Moorish Spain and across the Sahara from Timbuctoo. Even in the highly cultivated region of the lower slope of the Atlas there are groups of varied ethnic origin, the descendants of tribes transplanted by long-gone rulers and still preserving many of their original characteristics.

In the bazaars all these peoples meet and mingle: cattle-dealers, olive growers, peasants from the Atlas, the Souss and the Draa. Blue Men of the Sahara, blacks from Senegal and the Soudan, coming in to trade with the wool-merchants, tanners, leather- merchants, silk-weavers, armourers, and makers of agricultural implements.

Dark, fierce and fanatical are these narrow souks of Marrakech.

They are mere mud lanes roofed with rushes, as in South Tunisia and Timbuctoo, and the crowds swarming in them are so dense that it is hardly possible, at certain hours, to approach the tiny raised kennels where the merchants sit like idols among their wares. One feels at once that something more than the thought of bargaining – dear as this is to the African heart – animates these incessantly moving throngs. The souks of Marrakech seem, more than any others, the central organ of a native life that extends far beyond the city walls into secret clefts of the mountains and far-off

oases where plots are hatched and holy wars fomented – farther still, to yellow deserts whence negroes are secretly brought across the Atlas to that inmost recess of the bazaar where the ancient traffic in flesh and blood still surreptitiously goes on.

All these many threads of the native life, woven of greed and lust, of fetishism and fear and blind hate of the stranger, form, in the souks, a thick network in which at times one’s feet seem literally to stumble. Fanatics in sheep skins glowering from the guarded thresholds of the mosques, fierce tribesmen with inlaid arms in their belts and the fighters’ tufts of wiry hair escaping from camel’s-hair turbans, mad negroes standing stark naked in niches of the walls pouring down Soudanese incantations upon the fascinated crowd, consumptive Jews with pathos and cunning in their large eyes and smiling lips, lusty slave-girls with earthen oil-jars resting against swaying hips, almond-eyed boys leading fat merchants by the hand, and bare-legged Berber women, tattooed and insolently gay, trading their striped blankets, or bags of dried roses and irises, for sugar, tea or Manchester cottons – from all these hundreds of unknown and unknowable people, bound together by secret affinities, or intriguing against each other with secret hate, there emanated an atmosphere of mystery and menace more stifling than the smell of camels and spices and black bodies and smoking fry which hangs like a fog under the close roofing of the souks.

And suddenly one leaves the crowd and the turbid air for one of those quiet corners that are like the back-waters of the bazaar: a small square where a vine stretches across a shop-front and hangs ripe clusters of grapes through the reeds. In the patterning of grape-shadows a very old donkey, tethered to a stone-post, dozes under a pack-saddle that is never taken off; and near by, in a matted niche, sits a very old man in white. This is the chief of the Guild of ‘Morocco’ Workers of Marrakech, the most accomplished crafts- men in Morocco in the preparing and using of the skins to which the city gives its name. Of these sleek moroccos, cream-white or dyed with cochineal or pomegranate skins, are made the rich bags of the Chleuh dancing-boys, the embroidered slippers for the harem, the belts and harnesses that figure so largely in Moroccan trade – and of the finest, in old days, were made the pomegranate- red morocco bindings of European bibliophiles.

From this peaceful corner one passes into the barbaric splendor of a souk hung with innumerable plumy bunches of floss silk – skeins of citron yellow, crimson, grasshopper green and pure purple. This is the silk-spinners’ quarter, and next to it comes that of the dyers, with great seething vats into which the raw silk is plunged, and ropes overhead where the rainbow masses are hung out to dry. Another turn leads into the street of the metal workers and armourers, where the sunlight through the thatch flames on round flanks of beaten copper or picks out the silver bosses of ornate powder-flasks and pistols; and nearby is the souk of the ploughshares, crowded with peasants in rough Chleuh cloaks who are waiting to have their archaic ploughs repaired, and that of the smiths, in an outer lane of mud huts where negroes squat in the dust and sinewy naked figures in tattered loin cloths bend over blazing coals. And here ends the maze of the bazaar.

***

The Virago Book Of Women Travellers.

by Mary Morris

'A volume in which rich and unexpected seams of precious materials await discovery' Guardian

Three hundred years of wanderlust are captured in this collection as women travel for peril or pleasure, whether to gaze into Persian gardens or imbibe the French countryside, to challenge the fierce Sahara or climb an impossible mountain.

The extraordinary women in this collection are observers of the world in which they wander; their prose rich in description, remarkable in detail. Mary McCarthy conveys the vitality of Florence while Willa Cather's essay on Lavandou foreshadows her descriptions of the French countryside in later novels. Others are more active participants in the culture they are visiting, such as Leila Philip, as she harvests rice with Japanese women. Whether it is curiosity about the world, a thirst for adventure or escape from personal tragedy, all of these women are united in that they approached their journeys with wit, intelligence, compassion and empathy for the lives of those they encountered along the way.

Also includes writing by Willa Cather, Joan Didion, Vita Sackville-West, M. F. K Fisher, Christina Dodwell and more.